100 YEARS OF SEXTON BLAKE

by Norman Wright

The reading habits of the nation underwent profound changes during the late 19th century. Education for all, the continuing population movement from the countryside to the industrial towns and the development of cheaper printing processes resulted in the publication of a profusion of new periodicals to cater for a growing market that had the money to indulge in the occasional magazine or paper. For the better off there were publications such as The Strand Magazine, a trend-setting monthly of great influence, probably best remembered now for bringing Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories to a wide audience. The success of Holmes resulted in an upsurge of interest in the genre of crime fiction and the appearance in print of a great many imitations, most of them inferior to Doyle's definitive detective. Soon every periodical worth its salt had its own resident sleuth tracking miscreants through the London fogs and studying footprints through a large lens.

Earlier in the nineteenth century the only cheap reading matter available to the masses were 'penny bloods'; cheap part-works that revelled in gruesome fiction appealing to the lowest tastes. With such titles as "The Wild Boys of London", "Varney the Vampire" and "Sweeney Todd" they were invariably badly written and without exception full of murder, mayhem and blood-letting. With the advent of the publishing boom the 'bloods', or penny dreadfuls as they were sometimes called, lost ground and the final nail in their coffin was brought about by Alfred Harmsworth who published The Halfpenny Marvel, designed not only to undercut 'penny bloods' as far as price was concerned but also to provide young readers with more wholesome reading matter. The editorial of the first issue, published on 11th November 1893, made his intentions very clear... "The books of this library will contain nothing that is not pure and healthy — nothing that has a tendency other than to elevate; and they will, furthermore, form a healthy contrast to the deleterious rubbish known as the penny dreadful." The first few issues of "The Halfpenny Marvel" contained run of the mill adventure stories, full of blood and thunder and daring deeds, but lacking the gothic horror of the notorious bloods. It was in issue number five that the editor introduced Sexton Blake, announcing that the 'clever detective' would star in the following week’s story, entitled "The Missing Millionaire", a tale that no reader would be able to put down unfinished.

Earlier in the nineteenth century the only cheap reading matter available to the masses were 'penny bloods'; cheap part-works that revelled in gruesome fiction appealing to the lowest tastes. With such titles as "The Wild Boys of London", "Varney the Vampire" and "Sweeney Todd" they were invariably badly written and without exception full of murder, mayhem and blood-letting. With the advent of the publishing boom the 'bloods', or penny dreadfuls as they were sometimes called, lost ground and the final nail in their coffin was brought about by Alfred Harmsworth who published The Halfpenny Marvel, designed not only to undercut 'penny bloods' as far as price was concerned but also to provide young readers with more wholesome reading matter. The editorial of the first issue, published on 11th November 1893, made his intentions very clear... "The books of this library will contain nothing that is not pure and healthy — nothing that has a tendency other than to elevate; and they will, furthermore, form a healthy contrast to the deleterious rubbish known as the penny dreadful." The first few issues of "The Halfpenny Marvel" contained run of the mill adventure stories, full of blood and thunder and daring deeds, but lacking the gothic horror of the notorious bloods. It was in issue number five that the editor introduced Sexton Blake, announcing that the 'clever detective' would star in the following week’s story, entitled "The Missing Millionaire", a tale that no reader would be able to put down unfinished.

"The Missing Millionaire — The story of a Daring Detective" appeared in The Halfpenny Marvel for 15th December and was a quite unremarkable story upon which to build a legend. The portrayal of Blake was far removed from the hawk-faced fighter for justice that he became in the 1920s and 1930s. In his first adventure he was depicted as an avaricious character, rubbing his hands at the thought of the large fee he was going to receive from his rich client. Later in the story the Holmesian influence was apparent in an episode involving a street Arab, akin to the Baker Street Irregulars so beloved of Holmes, who helped Blake track down a kidnap victim. It is perhaps interesting to note that in the very week Blake was making his debut in the pages of the Halfpenny Marvel Sherlock Holmes was facing his Final Problem with Professor Moriarty at the edge of the Reichenback Falls in the pages of The Strand Magazine. The following weeks Halfpenny Marvel contained another Blake tale, "A Christmas Crime & The Mystery of Black Grange". As with the first tale it was an incredibly melodramatic story with dark villains, fair heroines and over the top dialogue worthy of Todd Slaughter. In the second chapter Blake fell in love and as the story came to a close he was on the point of asking the lady in question to marry him. But, detection and marriage did not seem to mix and fortunately for detection, and detective story enthusiasts, the lady in question slipped quietly into oblivion.

Two further Sexton Blake stories, "A Golden Ghost", and "Sexton Blake's Peril", appeared in The Halfpenny Marvel. All four tales were written by Harry Blyth, three of them under the pen name Hal Meredeth and one under his own name. Little is known of Blyth but according to "The Men Behind Boys Fiction" (Lofts and Adley 1970) he was born in 1852 and worked mainly as a freelance journalist. It was as a result of a series of articles entitled "Third Class Crimes", written for the Sunday People, that he was commissioned to write a series of detective stories for the Halfpenny Marvel. As it turned out Harmsworth got an incredibly good bargain, for the nine guinea fee they paid Blyth for the first story included payment for the copyright of the character! In addition to the four Blake adventures for the Halfpenny Marvel Blyth also wrote two stories of the detective for the Union Jack, a companion paper to The Halfpenny Marvel, launched by Harmsworth in April 1894. It was in the pages of Union Jack that Sexton Blake was to thrive and prosper.

"Sexton Blake — Detective" appeared in Union Jack number 2 and for the next year or so his adventures appeared spasmodically throughout the run of the halfpenny series of the weekly. When Union Jack increased in size and its price rose to one penny, in October 1903, Blake's appearances became more frequent and from number 95 he became the paper’s resident 'tec featuring in every issue until its metamorphosis into Detective Weekly in 1933. In those early adventures, when Union Jack sported a pink cover and incredibly tiny print, Blake was very much the Edwardian gentleman. The plots were often quite complex and in retrospect the stories, characters and plots offer a fascinating insight into the period — the ghettos of London, the sinister riverside docklands of Limehouse and, at the other extreme, the customs and formalities of 'society' people. Blake's popularity grew steadily throughout the decade and soon his exploits began to appear in other publications including Answers, Boys’ Friend and Penny Pictorial.

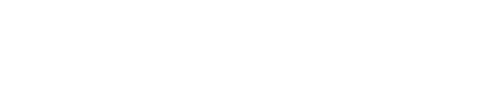

A good detective needs an assistant, someone to discuss the case with, send on errands and do all the donkey work. In the earliest stories Blake had a variety of helpers but with issue number 53, entitled "Cunning Against Skill", he found a permanent assistant. Tinker was a bright-eyed ragamuffin with the capacity to take a lot of rough with the smooth. He was a wiry youngster with plenty of common sense and a strong right hook that often stood him in good stead when the going got tough — as it often did. He was also useful to add a spot of light relief to the stories. The Union Jack was aimed at a predominantly juvenile market and the editor saw Tinker as a strong character with whom his young readers could identify. As the years progressed Tinker aged slightly and he became more sophisticated. During the 1930s he would drive Blake's car and pilot his aeroplane as well as continuing with the more mundane jobs included pasting newspaper cuttings into the detective's scrap-books and shadowing unsavoury characters. Tinker’s real name was not revealed until 1960 in a story entitled "Dead Man's Destiny".

A good detective needs an assistant, someone to discuss the case with, send on errands and do all the donkey work. In the earliest stories Blake had a variety of helpers but with issue number 53, entitled "Cunning Against Skill", he found a permanent assistant. Tinker was a bright-eyed ragamuffin with the capacity to take a lot of rough with the smooth. He was a wiry youngster with plenty of common sense and a strong right hook that often stood him in good stead when the going got tough — as it often did. He was also useful to add a spot of light relief to the stories. The Union Jack was aimed at a predominantly juvenile market and the editor saw Tinker as a strong character with whom his young readers could identify. As the years progressed Tinker aged slightly and he became more sophisticated. During the 1930s he would drive Blake's car and pilot his aeroplane as well as continuing with the more mundane jobs included pasting newspaper cuttings into the detective's scrap-books and shadowing unsavoury characters. Tinker’s real name was not revealed until 1960 in a story entitled "Dead Man's Destiny".

Another member of the team introduced early on in the canon was Pedro the bloodhound, who made his debut in Union Jack number 100, "The Dog Detective". In character he was something of a cross between Rin Tin Tin and Lassie and delivering a message, tracking a felon or saving a life or two was all in a day's work for him. In later years Pedro went into semi-retirement and seldom took much part in the action of the stories, being content instead to doze on the hearth rug in Blake's consulting room. One character who did stay active to the end was Mrs Bardell, Blake's garrulous housekeeper. She arrived in Edwardian times but went on to be something of a celebrity in a number of Christmas stories written during the 1930s by Gwyn Evans. She had a heart of gold and a wonderful way with the English language, adding more than a touch of humour to many a story with her hilarious malapropisms.

Another member of the team introduced early on in the canon was Pedro the bloodhound, who made his debut in Union Jack number 100, "The Dog Detective". In character he was something of a cross between Rin Tin Tin and Lassie and delivering a message, tracking a felon or saving a life or two was all in a day's work for him. In later years Pedro went into semi-retirement and seldom took much part in the action of the stories, being content instead to doze on the hearth rug in Blake's consulting room. One character who did stay active to the end was Mrs Bardell, Blake's garrulous housekeeper. She arrived in Edwardian times but went on to be something of a celebrity in a number of Christmas stories written during the 1930s by Gwyn Evans. She had a heart of gold and a wonderful way with the English language, adding more than a touch of humour to many a story with her hilarious malapropisms.

Over the years Blake often worked with the regular police force. In the very early stories Will Spearing was the Scotland Yard man who figured most frequently but probably the best, and certainly the most fondly remembered, was the bluff Inspector Coutts. Many stories began with him sitting in Blake's consulting room baffled at some mystery or other and seeking the detective's advice. He and Tinker would often indulge in friendly banter, each trying to get the better of the other. Such touches, and the many and varied characters found in the Blake saga, set it above the multitude of other detective tales found in British pulp fiction of the 1920s and 1930s.

Most of the Sexton Blake stories in the papers mentioned so far varied in length from between ten to twenty thousand words. But when a few extra long Blake stories of sixty to seventy thousand words appeared in the Boys’ Friend Library their popularity was such that in 1915 the Sexton Blake Library was launched giving readers regular monthly book length stories of the detective. The first number of the library was entitled "The Yellow Tiger" and was written by G.H. Teed, probably the most popular of the Blake authors of the period. Early issues of the Sexton Blake Library are very scarce and only a few copies of "The Yellow Tiger" are known to exist. Fortunately for collectors wishing to read the story a volume comprising the first four issues of the Sexton Blake Library was reprinted by Hawk Books in 1989 with a long introduction by the present writer. The Sexton Blake Library went from strength to strength and as the decades passed new writers added their own individual stamp to both the stories in the monthly issues of the Sexton Blake Library and to those in the Union Jack which still continued to print regular weekly adventures of the character. A number of writers, including John Creasey, cut their literary teeth writing Sexton Blake stories before going on to even greater success writing of their own characters.

Most of the Sexton Blake stories in the papers mentioned so far varied in length from between ten to twenty thousand words. But when a few extra long Blake stories of sixty to seventy thousand words appeared in the Boys’ Friend Library their popularity was such that in 1915 the Sexton Blake Library was launched giving readers regular monthly book length stories of the detective. The first number of the library was entitled "The Yellow Tiger" and was written by G.H. Teed, probably the most popular of the Blake authors of the period. Early issues of the Sexton Blake Library are very scarce and only a few copies of "The Yellow Tiger" are known to exist. Fortunately for collectors wishing to read the story a volume comprising the first four issues of the Sexton Blake Library was reprinted by Hawk Books in 1989 with a long introduction by the present writer. The Sexton Blake Library went from strength to strength and as the decades passed new writers added their own individual stamp to both the stories in the monthly issues of the Sexton Blake Library and to those in the Union Jack which still continued to print regular weekly adventures of the character. A number of writers, including John Creasey, cut their literary teeth writing Sexton Blake stories before going on to even greater success writing of their own characters.

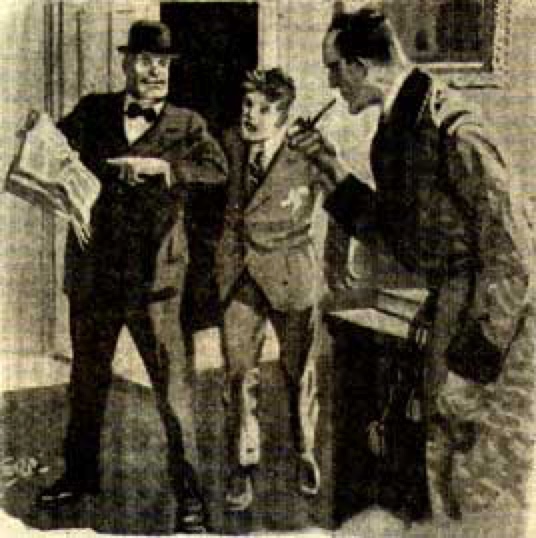

Over the years Blake faced a number of memorable villains, many of whom became almost as well known as the detective himself. One of the best was Waldo the Wonderman, a super-strong character who made his debut in the Xmas issue of Union Jack for 1918. Waldo was the creation of Edwy Brooks a prolific writer who penned dozens of Sexton Blake stories as well as hundreds of stories featuring another well remembered detective, Nelson Lee. Early on Waldo was an out and out villain, but as the years passed he mellowed until he and Blake were almost the best of friends. Waldo was still making appearances in the stories in 1940. Later Waldo became the model for Norman Conquest, a character created by Brooks for a long-running series of thriller novels published by Collins under his Berkeley Gray pen-name. Another favourite was Zenith the Albino — he of the immaculate evening dress and mesmerising voice — who first came to Blake's notice in the story entitled "A Duel to the Death", published in October 1919, when he made a dramatic entry into the detective's hotel room during a raging gale. The 'serial villains' — Waldo, Zenith, Leon Kestrel, George Marsden Plummer etc. became very popular and were frequently mentioned in bold type on the covers. The great disadvantage of stories featuring such characters was that the reader knew that at the end Blake was not going to be able to deal out the justice that was so often richly deserved. If the character was to appear again and again he could not be shut away behind prison bars for twenty years. For that reason many readers preferred stories that did not feature a regular villain and ended with the miscreant receiving his just deserts.

Over the years Blake faced a number of memorable villains, many of whom became almost as well known as the detective himself. One of the best was Waldo the Wonderman, a super-strong character who made his debut in the Xmas issue of Union Jack for 1918. Waldo was the creation of Edwy Brooks a prolific writer who penned dozens of Sexton Blake stories as well as hundreds of stories featuring another well remembered detective, Nelson Lee. Early on Waldo was an out and out villain, but as the years passed he mellowed until he and Blake were almost the best of friends. Waldo was still making appearances in the stories in 1940. Later Waldo became the model for Norman Conquest, a character created by Brooks for a long-running series of thriller novels published by Collins under his Berkeley Gray pen-name. Another favourite was Zenith the Albino — he of the immaculate evening dress and mesmerising voice — who first came to Blake's notice in the story entitled "A Duel to the Death", published in October 1919, when he made a dramatic entry into the detective's hotel room during a raging gale. The 'serial villains' — Waldo, Zenith, Leon Kestrel, George Marsden Plummer etc. became very popular and were frequently mentioned in bold type on the covers. The great disadvantage of stories featuring such characters was that the reader knew that at the end Blake was not going to be able to deal out the justice that was so often richly deserved. If the character was to appear again and again he could not be shut away behind prison bars for twenty years. For that reason many readers preferred stories that did not feature a regular villain and ended with the miscreant receiving his just deserts.

Blake's popularity was such that it was not long before his exploits were transferred to the stage. The first Blake play seems to have been “The Case of the Coiners", produced in 1907. Many others followed but probably the most famous was Donald Stuart's four-act play, "Sexton Blake", first performed in 1930 with Arthur Wontner as the detective. The play was published in story form in Union Jack in 1930 with a picture of Wontner as Blake on the cover. At about the same time Wontner made a 78rpm gramaphone record of a short Sexton Blake adventure entitled "Murder on the Portsmouth Road".

Blake's debut to the silver screen was a silent made in 1909 and entitled simply "Sexton Blake". A series of short films followed in 1914 and then a further series in 1928. A number of the latter series have survived and viewed today only serve to confirm that the detective story was not suited to the silent screen. In the early 1930s a number of sound films were made with George Curzon playing Blake. Of these at least "Sexton Blake and the Hooded Terror" has survived and shows a marked improvement over those made in the silent days. Curzon reprised his role of Blake in a radio serial, "Enter Sexton Blake", made by the BBC in 1939. A second radio serial, "A Case for Sexton Blake", followed a year later. Further Blake films were made in later years but by and large they were second features cheaply and quickly made and just as quickly forgotten.

Blake's debut to the silver screen was a silent made in 1909 and entitled simply "Sexton Blake". A series of short films followed in 1914 and then a further series in 1928. A number of the latter series have survived and viewed today only serve to confirm that the detective story was not suited to the silent screen. In the early 1930s a number of sound films were made with George Curzon playing Blake. Of these at least "Sexton Blake and the Hooded Terror" has survived and shows a marked improvement over those made in the silent days. Curzon reprised his role of Blake in a radio serial, "Enter Sexton Blake", made by the BBC in 1939. A second radio serial, "A Case for Sexton Blake", followed a year later. Further Blake films were made in later years but by and large they were second features cheaply and quickly made and just as quickly forgotten.

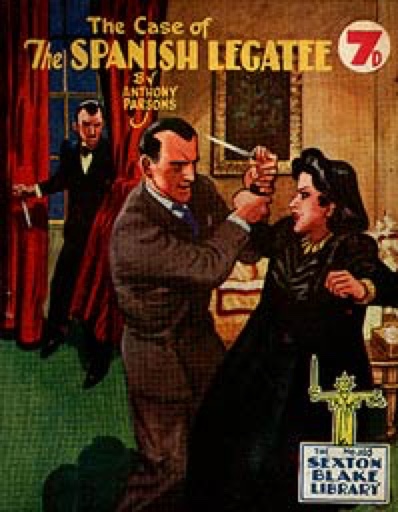

The definitive visual image of Sexton Blake was established by Eric Parker, a prolific artist who began illustrating the detective's adventures in Union Jack in 1922. Prior to that time a number of artists had contributed to the saga but throughout the 1920s Parker's depiction became the one that has remained associated with Blake. He portrayed him along the lines of Paget's Holmes, with hawk-like chin and high forehead, but he also gave him a glint in his eyes and a lithe, panther-like quality. His Blake was still a thinker, but every inch a man of action as well. Parker's distinctive style was instantly recognisable and had a great appeal to readers. "Why can't Eric Parker illustrate every Blake adventure?" was typical of the sort of letter that readers sent in when Parker was absent from the pages of Union Jack for a few weeks. In 1926 Parker modelled a bust of Sexton Blake. Readers could obtain one of the plaster models by introducing a certain number of their friends to Union Jack. The bust was beautifully sculptured and I was surprised to learn from Parker's daughter a few years ago that it was the first time her father had ever attempted such work. The bust even featured in a story, "The Case of the Sexton Blake Bust", published in Union Jack in March 1926. In 1929 Parker began painting the full colour covers for the Sexton Blake Library and in a period lasting almost thirty years he painted nearly 900 covers for the publication.

The definitive visual image of Sexton Blake was established by Eric Parker, a prolific artist who began illustrating the detective's adventures in Union Jack in 1922. Prior to that time a number of artists had contributed to the saga but throughout the 1920s Parker's depiction became the one that has remained associated with Blake. He portrayed him along the lines of Paget's Holmes, with hawk-like chin and high forehead, but he also gave him a glint in his eyes and a lithe, panther-like quality. His Blake was still a thinker, but every inch a man of action as well. Parker's distinctive style was instantly recognisable and had a great appeal to readers. "Why can't Eric Parker illustrate every Blake adventure?" was typical of the sort of letter that readers sent in when Parker was absent from the pages of Union Jack for a few weeks. In 1926 Parker modelled a bust of Sexton Blake. Readers could obtain one of the plaster models by introducing a certain number of their friends to Union Jack. The bust was beautifully sculptured and I was surprised to learn from Parker's daughter a few years ago that it was the first time her father had ever attempted such work. The bust even featured in a story, "The Case of the Sexton Blake Bust", published in Union Jack in March 1926. In 1929 Parker began painting the full colour covers for the Sexton Blake Library and in a period lasting almost thirty years he painted nearly 900 covers for the publication.

In 1933 Union Jack was given a face-lift and re-titled Detective Weekly. The cover of the first issue bore a splendidly atmospheric portrait of Blake sitting at his desk, gun in one hand, telephone receiver in the other. "Get Me Scotland Yard Quick" read the caption. The story was entitled "Sexton Blake's Secret" and dealt with Blake's wayward brother, Nigel. The detective seems to have been unfortunate with his kin for the very first long Blake story, "Sexton Blake's Honour", published in the Boys’ Friend Library in 1907, had also concerned a ne’er-do-well brother. Blake's adventures continued in Detective Weekly until 1935 when it was decided to drop the character in favour of stories featuring other detectives. But the change did not last long and in 1937 Blake made a triumphant return due to popular demand. The following year the first of four "Sexton Blake Annuals" was published and had it not been for paper rationing brought about by the war it is likely that the annual would have continued for many years. Another casualty of the conflict was Detective Weekly itself, which came to an end in May 1940.

In 1933 Union Jack was given a face-lift and re-titled Detective Weekly. The cover of the first issue bore a splendidly atmospheric portrait of Blake sitting at his desk, gun in one hand, telephone receiver in the other. "Get Me Scotland Yard Quick" read the caption. The story was entitled "Sexton Blake's Secret" and dealt with Blake's wayward brother, Nigel. The detective seems to have been unfortunate with his kin for the very first long Blake story, "Sexton Blake's Honour", published in the Boys’ Friend Library in 1907, had also concerned a ne’er-do-well brother. Blake's adventures continued in Detective Weekly until 1935 when it was decided to drop the character in favour of stories featuring other detectives. But the change did not last long and in 1937 Blake made a triumphant return due to popular demand. The following year the first of four "Sexton Blake Annuals" was published and had it not been for paper rationing brought about by the war it is likely that the annual would have continued for many years. Another casualty of the conflict was Detective Weekly itself, which came to an end in May 1940.

Despite the ending of Detective Weekly Blake still continued to entertain thousands of readers every month in the Sexton Blake Library and in the pages of Knock-Out Comic where his exploits were depicted in picture strip form drawn initially by Jos Walker and later by Alfred Taylor, who continued the strip for ten years. In 1949 Eric Parker made his one contribution with a splendidly drawn adventure strip serial entitled "The Secret of Monte Cristo".

During the early years of the 1950s the standard of stories published in the Sexton Blake Library suffered a decline. The publication was beginning to look old fashioned, the monthly stories were being ground out by just a handful of tired writers and sales were falling. The fact that it survived and was given a new lease of life was due to William Howard Baker who took over as editor in 1956. He gave the library a complete face-lift, moving Blake and Tinker to swish new offices in Berkeley Square and giving the detective a secretary. The stories became tougher and Blake developed a more hard-boiled approach to criminals. The covers became noticeably different too with long-legged blondes giving the covers an eye-catching appeal.

Whatever long-standing Blake enthusiasts thought of the changes they certainly encouraged new readers and the library continued until 1963 when the final issue, nostalgically entitled "The Last Tiger", was published. It looked like the end of regular adventures of Sexton Blake but he bounced back two years later in a series of regular format paperbacks edited by Howard Baker and published by Mayflower Books. The character was still as popular as ever during the 1960s and the BBC produced a new series of radio plays with William Franklyn taking the part of the detective. On television Lawrence Payne portrayed Blake in a series of adventures set in the 1920 and to accompany the TV series an adventure strips based on the characters appeared in Valiant. In the 1970s Blake made another television appearance in "Sexton Blake and the Demon God", a period serial adventure complete with 'cliff-hanger' endings to each episode.

No new stories of the detective have appeared for fifteen years, but several anthologies of his classic cases have been published recently and interest in collecting issues of the Sexton Blake Library seems to be on the increase. Carnival Films, makers of the excellent "Poirot" television series, are considering producing a series based on the exploits of Sexton Blake and if it does materialise it will be a fitting and well deserved centenary celebration of one of the best loved fictional detectives of all time.*

*Sadly, it was never made.