THE OTHER BAKER STREET DETECTIVE

by Derek Hinrich

In the autumn of 1903 Mr Sherlock Holmes, now rising fifty, retired from a practice which had become wearisome to him and settled in a cottage on the South Downs, five miles from Eastbourne and in sight of the sea, to keep bees and, no doubt - as the humour took him — to begin to draft that promised magnum opus of his declining years, The Whole Art of Detection.

At about the same time, by one of those strange coincidences which were so often to characterise their careers, that other celebrated detective, Mr Sexton Blake, exhausted by prolonged overwork in rounding up The Brotherhood of Silence and other malefactors, dismissed all his staff except for his new page-boy (a cheery urchin known as Tinker whom he had recently rescued from a life on the streets), closed his office and, under the name of Henry Park, retired to a cottage in the secluded village of Brampton Stoke. There he, too, contemplated life as an apiarist. After some months, however, his idyll was shattered by a sudden charge of theft levelled against him by Sir George Clinton, the squire of Brampton Stoke (I have been unable to find this village in any gazetteer but as its neighbourhood was served by trains from Euston, it is probably somewhere in the West Midlands). Poor Mr Park evaded arrest but Sir George Clinton then sought Sexton Blake's help in tracking him down. Blake, moved by the irony of this novel commission, determined to use it to clear his alter ego and find the real culprit. With Tinker's help, he was successful and returned, reinvigorated, to his practice, which he was to continue to pursue for another 66 years to the confusion of the criminal classes world-wide.

Lest it be thought that this adventure of Mr Blake's was in part an exercise in plagiarism, let me point out that the account of his temporary retirement was published in The Union Jack of 15th October 1904 (in the story "Cunning Against Skill"), nearly two months before Mr Holmes's was announced in The Strand Magazine in "The Adventure of The Second Stain".

It is strange that the name of Sexton Blake is so lightly regarded now. There was a time — in the 'twenties and 'thirties — when to many he was the Baker Street Detective. As E S Turner points out in his chapter on Sexton Blake in his seminal study of boys' stories, Boys Will Be Boys, "There was once a radio quiz in which a girl was asked to name a famous detective who lived in Baker Street. Her reply 'Sexton Blake' did not satisfy the BBC quizmaster, though in thousands of homes it was doubtless accepted as the right answer. Even when the quizmaster resorted to transparent prompting — 'No, I mean some detective or detectives who had homes in Baker Street,' the girl obstinately clung to her original reply." I remember hearing this myself: it was in one of the radio shows for the Forces in 1944 or '45.

Sexton Blake did not live or work in Baker Street when his first recorded case appeared in Mr Alfred Harmsworth's new story paper, The Halfpenny Marvel, in December 1893 — the very same month that readers of The Strand Magazine were devastated by the news of the apparent death of Sherlock Holmes at the hands of Professor Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls.

Blake, The Marvel's readers were told, “Belonged to the new order of detectives. He possessed a highly cultivated mind, which helped to support his active courage. His refined clean-shaven face readily lent itself to any disguise, and his mobile features assisted to clinch any facial illusion he desired to produce". His office was at first in New Inn Chambers but he subsequently shared another in Wych Street, off the Strand, with a French partner, Jules Gervaise. In these early cases Blake and Gervaise encountered several notable villains: they were instrumental, for instance, in breaking up three criminal confederacies known respectively as "The Red Lights of London", "The Assassins of the Seine", and "The Terrible Three". These early adventures, though each only of some 25,000 words, are as full of incident as any three volume "sensation" novel by Miss Braddon and the villains all came to suitably sticky ends (literally so in one case of Gervaise's where the culprit fell into a barrel of boiling pitch).

The first stories were written by a young journalist, Harry Blyth, some of whose work in The People had been noticed by Harmsworth. Not only did Harmsworth commission the stories but he also bought with them the copyright of the name of Sexton Blake, all for nine guineas. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle might lament the sale of the copyright of A Study In Scarlet for £25 - how much more might Blyth have regretted selling his rights to Sexton Blake if he had had any inkling of what was to come, but he sadly died of typhoid not long after. Mark you, it is said that Blake's christian name was originally to have been "Frank" and "Sexton" was the inspired choice of an editorial conference: a rather better example of committee work than the old canard that a committee briefed to design a horse would produce a camel.

Gervaise apparently soon retired but not before Blake had defined the principles governing the conduct of the partnership: "If you look for any dishonourable work at our hands you may spare your own words and our time. We do not interfere in disputes between man and wife, nor do we pursue defaulting clerks. But if there is a wrong to be righted, an evil to be redressed, or a rescue of the weak and the suffering from the powerful, our hearty assistance can be readily obtained. We do nothing for hire here; we would cheerfully undertake to perform without fee or reward. But when our clients are wealthy we are not so unjust to ourselves as to make a gratuitous offer of our services."

Gervaise apparently soon retired but not before Blake had defined the principles governing the conduct of the partnership: "If you look for any dishonourable work at our hands you may spare your own words and our time. We do not interfere in disputes between man and wife, nor do we pursue defaulting clerks. But if there is a wrong to be righted, an evil to be redressed, or a rescue of the weak and the suffering from the powerful, our hearty assistance can be readily obtained. We do nothing for hire here; we would cheerfully undertake to perform without fee or reward. But when our clients are wealthy we are not so unjust to ourselves as to make a gratuitous offer of our services."

Or, as Sherlock Holmes told "The Gold King", J. Neil Gibson, "My professional fees are upon a fixed scale. I do not vary them, save when I remit them altogether."

Philip Marlowe was more prosaic, "Twenty five dollars a day plus expenses, mostly gasoline and whisky."

No detective, however, can operate successfully for long in single harness and Sexton Blake over the next ten years, before Tinker came on the scene, had several fleeting assistants. One of these was a pidgin-speaking Chinese lad who provided light relief in what would now be deemed a highly politically incorrect fashion. He did not last long, though. His name, Wee-we, probably did not help. Then there was a waif named Griff and someone called Wallace Lorrimer, but none of these survived the purge of 1903-4.

When Sexton Blake first came to London he is said to have taken lodgings in Islington near the Angel. I have little knowledge of this period of his career but from "The Mystery of Hilton Royal", published in the Christmas 1904 issue of The Union Jack, it appears that he moved to Baker Street shortly before October 1903, that is to say on his return to practice following the affair at Brampton Stoke.

His residence in Baker Street can thus have only briefly overlapped with that of Mr Holmes.

At that time, however, Blake only occupied rooms and had a (nameless) landlady. It was not until 1905 that he began to enjoy the services of his splendidly malapropish housekeeper, Mrs Bardell, a motherly soul with a bun and a penchant for black bombazine. The presumption must be that his practice then was such as to enable him to acquire either the freehold or the lease of other premises in Baker Street for his sole occupation.

By that time, too, an admirer with the picturesque sobriquet of Nemo (no relation, apparently, of the captain of the Nautilus) had given him the bloodhound, Pedro. With these additions his household and team became complete for the next 51 years. It was a much cosier and more domestic ménage than that at 221B with Blake and Mrs Bardell, in effect, acting as the surrogate parents of Tinker (indeed in "The Mystery of Hilton Royal" it is said that Blake had adopted the seventeen years old Tinker as his son, but no other chronicler appears to have noticed this!) while that youth himself provided a character that the then juvenile readership might identify with.

Its exact location has been well protected. The address was 252 Upper Baker Street, which should put it on the other side of the road from 221B and slightly to its north, but the even numbers in Baker Street do not, I believe, exceed 240.

Sherlock Holmes was in active practice for 23 years and we have Watson's detailed accounts of 60 of his cases and mention of over 100 others, which are not related; while Holmes himself referred to his involvement in 500 of capital importance. In the twelve or so years between 1893 and his move to Baker Street, there are a trifle over 50 published accounts of Sexton Blake's cases in various journals, but after The Union Jack became devoted entirely to his adventures in 1905 (Sexton Blake's Own Paper, its by-line) and the change in his address, his practice burgeoned.

In the next 65 years over 3,500 accounts of his cases were published either in short story or in novel form in either The Union Jack or The Detective Weekly, or the various series of The Sexton Blake Library: a formidable workload. More than two hundred authors delved into his files and over 200,000,000 words were devoted to his adventures, probably more than has been written about any other single character; a literary phenomenon in fact.

In the next 65 years over 3,500 accounts of his cases were published either in short story or in novel form in either The Union Jack or The Detective Weekly, or the various series of The Sexton Blake Library: a formidable workload. More than two hundred authors delved into his files and over 200,000,000 words were devoted to his adventures, probably more than has been written about any other single character; a literary phenomenon in fact.

While the earlier adventures were intended for the juvenile reader, leading to the early slur that he was the "office boy's Sherlock Holmes", by his heyday in the 'twenties and 'thirties stories of Sexton Blake were directed equally at the "boy who's half a man or the man who's half a boy". Many of the authors at this period were also producers of popular hardback thriller fiction. Many of them indeed "de-Blaked" their stories of the great man and published them with renamed heroes through such firms as Wright and Brown, principally for the private circulating library trade so prevalent before the Second World War. A few even managed later to re-Blake such a book and sell it, with a change of title, all over again to the Amalgamated Press...

Mr Blake's change of address was no doubt inspired by a profound admiration for his senior colleague and the distinction which he had lent to Baker Street. Besides, it was once common for different trades and professions to congregate in certain streets of the capital: eminent doctors in Harley Street; fashionable tailors in Savile Row; furniture shops in the Tottenham Court Road.

It was appropriate, too, for him to move thither as he was surely now the doyen of his profession in London, as Sherlock Holmes had been before him. There was no one else of comparable stature then practising. Martin Hewitt was simply not in the same class; Dr Thorndyke had not yet taken chambers in King's Bench Walk; and that strange old man with the piece of string was not yet haunting the ABC tea-shop in Norfolk Street. It was true that Nelson Lee was at work in the Gray's Inn Road but he was not as active as Blake (neither had he yet adopted his other profession of schoolmaster).

Sexton Blake and his household was the happy subject of a remarkably slow ageing process. In 1893 he was apparently in his middle twenties. In 1907 he was about thirty and for much of the time when he was at the height of his powers, in the 1920s and '30s, he appeared only a few years older, and possibly had attained the early forties by 1970 when he retired. His loyal assistant and later partner, Tinker, aged about ten years between 1904 and 1970, while Mrs Bardell and Pedro remained outwardly the same throughout. Perhaps only the Man in Half Moon Street glimpsed his secret (He was, after all, created by a chronicler of Blake).

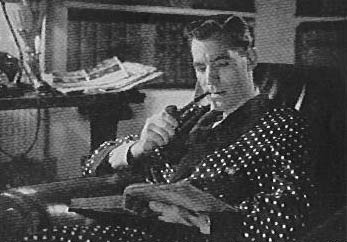

One of the unfortunate features of the saga of Sexton Blake is the lack for many years of a definitive likeness of the man. He was sadly not blessed with a counterpart of Sidney Paget or Frederick Dorr Steele until the middle 'twenties when Eric Parker became his principal illustrator. In 1893 Blake was a sturdy, side-whiskered young man in a billycock and an ulster carrying an ashplant. Over the years, particularly once he had moved to Baker Street, he fined down, becoming much leaner. By 1913 he had a faintly Napoleonic air but his later, Parker, portraits reveal a more ascetic face altogether. At the same time he took more and more to a pipe (smoking is said to be an aid to slimming isn't it?), was known to try his hand at a violin and to prefer a dressing gown when sitting and pondering. Unlike his predecessor, he never wittingly took drugs, though occasionally opponents administered them by artifice.

One of the unfortunate features of the saga of Sexton Blake is the lack for many years of a definitive likeness of the man. He was sadly not blessed with a counterpart of Sidney Paget or Frederick Dorr Steele until the middle 'twenties when Eric Parker became his principal illustrator. In 1893 Blake was a sturdy, side-whiskered young man in a billycock and an ulster carrying an ashplant. Over the years, particularly once he had moved to Baker Street, he fined down, becoming much leaner. By 1913 he had a faintly Napoleonic air but his later, Parker, portraits reveal a more ascetic face altogether. At the same time he took more and more to a pipe (smoking is said to be an aid to slimming isn't it?), was known to try his hand at a violin and to prefer a dressing gown when sitting and pondering. Unlike his predecessor, he never wittingly took drugs, though occasionally opponents administered them by artifice.

He was undoubtedly blessed with an exceptionally strong constitution and a high degree of physical fitness - very necessary when one considers the perils he encountered throughout his long career. The occasions when Sherlock Holmes actually encountered physical violence in the accounts we possess are few, but with Sexton Blake it was an almost routine occurrence in every investigation. One can only stand in awe of a man who could take so much punishment without his faculties becoming impaired: a legion of prizefighters would not have withstood it.

Once comfortably ensconced in Baker Street, Sexton Blake devoted himself single-mindedly to his fight against crime. It took him to all quarters of the globe, for his practice was far more extensive than Holmes's. Many of his historians were men who had travelled widely and had extensive knowledge of Africa, India, the Americas and the Far East. He was loyally assisted by Tinker who also maintained the multi-volumed index of newspaper cuttings, which both in scope and size far exceeded Holmes's similar commonplace book; while that admirable woman, Mrs Bardell, kept house, cooked superbly, and maltreated English majestically. For example," Mr Blake", she would say, "is a master sluice who Scotland Yard defectives, Indian rajas and other Eastern potatoes constantly insult".

Sexton Blake's relations with Scotland Yard were mainly cordial except for those trying times in 1907 and 1933 when first his elder brother Henry and then his younger brother Nigel, were revealed to be dangerous criminals. Henry eventually committed suicide, sacrificing himself to save his brother's reputation, but Nigel had to be committed to a private asylum where, by one account, he presently died of pneumonia: according to another, later version, however, he recovered, was recruited to the secret service and was murdered by traitors in Calcutta in 1942. Such are the confusions of many hands at work upon a saga.

It was in the course of the narrative of Sexton Blake's struggle with his brother Nigel (in 1933, in the first issues of The Detective Weekly, the successor paper to The Union Jack) that we learned that Sexton Blake was the son of the distinguished Harley Street surgeon, Sir Berkeley Blake, had attended both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, had qualified as both a doctor of medicine and as a barrister, and was the author of several criminological monographs.

At the outset of the Birlstone case, Sherlock Holmes recommended to Inspector MacDonald the advisability of studying criminal history since "Everything comes in circles...The old wheel turns and the same spoke comes up. It's all been done before and will be again..."

There were certainly times when Sexton Blake encountered problems reminiscent of his illustrious predecessor. In 1908, for example, he prevented Detective Sergeant George Marsden Plummer from murdering his way to the earldom of Sevenoaks in a rather more forthright manner than that adopted to satisfy a similar ambition by Rodger Baskerville, alias Vandeleur, alias Stapleton. Plummer escaped from the gallows and prison to become an inveterate enemy of Blake, returning to plague him more than a hundred times over the next thirty years. The Scotland Yard renegade was a most versatile villain, at one stage even becoming the right hand man of Abdel Krim, the leader of the Riffs in the great Moroccan rebellion in the 'twenties.

There were certainly times when Sexton Blake encountered problems reminiscent of his illustrious predecessor. In 1908, for example, he prevented Detective Sergeant George Marsden Plummer from murdering his way to the earldom of Sevenoaks in a rather more forthright manner than that adopted to satisfy a similar ambition by Rodger Baskerville, alias Vandeleur, alias Stapleton. Plummer escaped from the gallows and prison to become an inveterate enemy of Blake, returning to plague him more than a hundred times over the next thirty years. The Scotland Yard renegade was a most versatile villain, at one stage even becoming the right hand man of Abdel Krim, the leader of the Riffs in the great Moroccan rebellion in the 'twenties.

In 1915, when in pursuit of the American criminal turned Austrian spy, Ezra Q Maitland, Blake found himself called upon amongst other matters to solve the Ritual of the Normanvilles (a family catechism beginning "Whose is it?/ His who was slain/ Why must ye seek?... ” which, when unravelled, led to a buried treasure (it is strange, is it not, how ancient families so often share similar traditions?).

Again, in 1932 Sexton Blake, in investigating a mysterious death had cause to note, as Holmes did "in the dreadful business of the Abernetty family", the depth to which the parsley had sunk into the butter upon a summer's day.

The old wheel indeed turned with a vengeance upon occasion.

Like many another popular hero, Sexton Blake was soon impersonated on the stage and a little later in the cinema; and he had the distinction of appearing in a serial on the BBC radio in 1938 - five years before Mr Holmes ever graced the British air waves. A television series set in the 'thirties followed in 1968 and '69.

Progressively from 1910, ten or more plays or dramatic sketches were performed in theatres or music halls around the country. Many of these continued in provincial repertories into the post-1918 period. None of them reached the West End, but a play, Sexton Blake, by Gerald Verner did have a substantial run there in 1930. The title role was played by Arthur Wontner and his success in it led to his being cast as Sherlock Holmes in a series of films in which he was acclaimed as one of the great interpreters of the senior man in Baker Street. Wontner also starred as Blake in a gramophone record playlet, Murder on The Portsmouth Road.

Sexton BlakeIn the eleven years 1909-1919 thirteen Sexton Blake films were made in Britain by various companies. A further series of six silent films were made in 1928 and '29 with Langhorne Burton as Blake and half a dozen sound films have been made at intervals, the last in 1960. One of these, Sexton Blake and The Hooded Terror of 1938, is preserved in the National Film Archive. He also enjoyed the distinction of being parodied — a sure sign of "arrival" - in two silent comedies, while a Baker Street hybrid, "Sherlock Blake" appeared in another in 1919.

Sexton BlakeIn the eleven years 1909-1919 thirteen Sexton Blake films were made in Britain by various companies. A further series of six silent films were made in 1928 and '29 with Langhorne Burton as Blake and half a dozen sound films have been made at intervals, the last in 1960. One of these, Sexton Blake and The Hooded Terror of 1938, is preserved in the National Film Archive. He also enjoyed the distinction of being parodied — a sure sign of "arrival" - in two silent comedies, while a Baker Street hybrid, "Sherlock Blake" appeared in another in 1919.

Holmes's cases contain a surprisingly high proportion of dubious military men: no less than eight criminal colonels, including of course Colonel Sebastian Moran who also figured in that truly remarkable collection of Ms amongst whom, before all others stood the transcendent figure of Professor Moriarty, the Napoleon of Crime, the Master Criminal.

Blake, however, was beset by crooked doctors ("When a doctor goes wrong he is the first of criminals.") - Drs Ferraro, Lepperman, Huxton Rymer, Satira, and Professor Kew were recurrent opponents. And as for Master Criminals, they came not single spies but by battalions: so many of them so called to distinguish them from ordinary criminals that one almost wonders if there was an organisation somewhere issuing diplomas (perhaps the Criminals Confederation, a world-wide conspiracy and another frequent opponent of Blake's, obliged).

The criminals Blake encountered were certainly no less sinister than those Sherlock Holmes met with but they generally tended towards a rather more flamboyant villainy and background. In his very first case back in 1893, for example, one of the "Red Lights of London" gang was a young transvestite rogue who led a double life as himself and "his sister", while in the inter-war years the notorious Monsieur Zenith - Zenith the Albino — who despite being wanted by the police of five continents, invariably dressed at all times of day or night in impeccable full evening dress of white tie and tails, was a cadet of the Roumanian branch of the House of Hohenzollern: while the Ace, the head of the Double Four Gang (their badge being a domino of that denomination), when unmasked, was found to be King Karl of Serbovia.

Only three men are known to have tried conclusions with Sherlock Holmes more than once — John Clay, Professor Moriarty, and Colonel Moran — but Sexton Blake's principal opponents were far more resilient. Time after time they were defeated but managed to escape at the last moment to return on some other occasion. Even when arrested on capital charges they managed to elude the rope. Though taken bang to rights in 1908, the aforementioned George Marsden Plummer (the doyen of them all), for example, survived to cross swords with Blake on a further 111 occasions up to 1940. With the others it was the same. Prince Wu Ling, the head of the Brotherhood of the Yellow Beetle intent, like Dr Fu-Manchu, on overthrowing Western power (and a far more convincing embodiment of the Yellow Peril than the evil doctor); Dr. Huxton Rymer; Leon Kestrel the Master Mummer; the hydra-headed Criminals Confederation and many others, continually wove fresh plots only to be thwarted yet again.

Then there was a positive menagerie of sinister individuals to confront — The Black Rat, The Black Eagle, The Owl, The Snake, The Spider, and The Scorpion, not to mention The Bat (though he later reformed and joined the side of the angels). There were various groups — The Black Trinity, The League of The Cobblers’ Last, The Council of Eleven - not to be confused with The Council of Nine — The League of Robin Hood, The Shadow Club, and a sinister group of itinerant Frenchmen bent on restoring the French monarchy — The League of The Onion Men.

The distaff side must not be neglected. Throughout his Golden Age Sexton Blake encountered a number of femmes fatales. The majority of these young ladies were adventuresses determined to avenge wrongs inflicted on their families by swindlers, but they presented problems for Blake, both criminal and emotional but fortunately for his readership, he never succumbed to any possible romantic entanglements they presented. Amongst such personages may be mentioned Mesdemoiselles Yvonne Cartier and Roxanne Harfield (who despite their French address were respectively Australian and Canadian), June Severance and Olga Nasmyth, "the girl of destiny", and the young lady with but six months to live who called herself Miss Death and wore a skull mask of silk. Time does not permit me to enlarge on these ladies, nor upon the female accomplices of Huxton Rymer, Mary Trent and the octoroon queen of crime in the Caribbean, Marie Galante; or the Indo-Chinese dancer Mali Vata-Mali, the equally exotic associate of the Scotland Yard renegade, George Marsden Plummer.

The distaff side must not be neglected. Throughout his Golden Age Sexton Blake encountered a number of femmes fatales. The majority of these young ladies were adventuresses determined to avenge wrongs inflicted on their families by swindlers, but they presented problems for Blake, both criminal and emotional but fortunately for his readership, he never succumbed to any possible romantic entanglements they presented. Amongst such personages may be mentioned Mesdemoiselles Yvonne Cartier and Roxanne Harfield (who despite their French address were respectively Australian and Canadian), June Severance and Olga Nasmyth, "the girl of destiny", and the young lady with but six months to live who called herself Miss Death and wore a skull mask of silk. Time does not permit me to enlarge on these ladies, nor upon the female accomplices of Huxton Rymer, Mary Trent and the octoroon queen of crime in the Caribbean, Marie Galante; or the Indo-Chinese dancer Mali Vata-Mali, the equally exotic associate of the Scotland Yard renegade, George Marsden Plummer.

Most of these characters were the invention and preserve of particular writers, though some were so popular that they were taken over by others as the originator dropped out. This was most notably the case with the senior villain, George Marsden Plummer, whose crimes were related by four different authors in succession. With the Baker Street household established, authors eager to make their mark on the saga and to assert their individuality had two courses open to them. One was to create their own distinctive adversary for Blake and the other was to introduce into their plots their own subsidiary hero or heroine to assist Blake in his battles, as Dorothy L Sayers first contemplated using Lord Peter Wimsey. There were many of these — for instance Gwyn Evans' journalist "Splash" Page, or John G Brandon's Honourable Ronald Sturges Vereker Purvale, known as RSVP, and Robert Murray Graydon's Inspector Coutts whom everyone took up (poor Coutts — fifty years of loyal cooperation but only the one promotion to Chief Inspector!), but master criminals predominated.

Amongst these, Leon Kestrel presented a special problem. Originally a rising star of the American theatre, he went to the bad and became a criminal of genius and daring and a master of disguise whose real face no one knew. He complicated matters on occasion by disguising himself as Sexton Blake, who once retaliated by disguising himself as Kestrel in disguise to impose on Kestrel's gang — a course of action with almost infinite possibilities.

In 1956 for the first time in fifty years the Sexton Blake saga was given a face-lift. Blake had been more and more in the doldrums since the outbreak of the Second World War. Three of the best writers had died suddenly between 1937 and 1939. Another, Anthony Skene — otherwise G N Phillips, a Quantity Surveyor in the then Office of Works, the creator of Zenith the Albino, who wrote some 120 Sexton Blake stories as a side-line — was too busy with his official duties to contribute more than two tales after 1939.

So in 1956, W Howard Baker, the editor of The Sexton Blake Library, dusted off Blake's image and the wheel turned and the same spoke came up again. In 1893 Blake and Gervaise had "a clerks' office with three doors". Now Blake became the head of the Sexton Blake Organisation with offices in Berkeley Square. Tinker's full name was revealed as Edward Carter (which was odd because in 1944 his surname was said to be Smith, although of course, as previously noted, it might have been Blake since 1903) and was recognised as junior partner. Blake acquired a glamorous secretary, Paula Dane, a dolly bird receptionist, Marion Lang, and a lady of more mature years, Miss Pringle, as bookkeeper. The staff was completed by the office cat, Millie, a Siamese who thankfully was on good terms with Pedro. The stalwart Chief Inspector Coutts continued to represent the Yard in most cases and Mrs Bardell remained to keep house in Baker Street. The lower floors there now became suites of offices occupied by various firms, but Blake and Tinker retained penthouse flats.

So in 1956, W Howard Baker, the editor of The Sexton Blake Library, dusted off Blake's image and the wheel turned and the same spoke came up again. In 1893 Blake and Gervaise had "a clerks' office with three doors". Now Blake became the head of the Sexton Blake Organisation with offices in Berkeley Square. Tinker's full name was revealed as Edward Carter (which was odd because in 1944 his surname was said to be Smith, although of course, as previously noted, it might have been Blake since 1903) and was recognised as junior partner. Blake acquired a glamorous secretary, Paula Dane, a dolly bird receptionist, Marion Lang, and a lady of more mature years, Miss Pringle, as bookkeeper. The staff was completed by the office cat, Millie, a Siamese who thankfully was on good terms with Pedro. The stalwart Chief Inspector Coutts continued to represent the Yard in most cases and Mrs Bardell remained to keep house in Baker Street. The lower floors there now became suites of offices occupied by various firms, but Blake and Tinker retained penthouse flats.

These changes gave Sexton Blake another 14 years of life. He did not die but gently faded away as publication of his adventures gradually faltered and then finally stopped.

These last years are not generally regarded with a great deal of favour by the majority of collectors who, in the main, are traditionalists and have nostalgic yearnings for Sexton Blake's "golden age" between the two world wars and for the few years immediately before 1914 when the classic period began to be shaped.

It was in those days he achieved his greatest fame and came to be thought of by his devotees as The Great Baker Street Detective. Many of his admirers also felt that their hero was regarded with quite unjustified and snobbish contempt in some quarters. They could, however, take comfort from the words of Dorothy L Sayers who, in a lecture, said of the adventures of Sexton Blake, “... they represent the nearest modern approach to a national folk-lore, conceived as the centre for a cycle of loosely connected romances in the Arthurian manner..."

Now no one could enjoy the Sherlock Holmes stories more than I, and I collect and enjoy the adventures of Sexton Blake. For my part I hope that one day we might see another statue on the opposite corner of Baker Street to the Other Great Detective. But as to chosing between them, then:

"God bless the King, I mean the Faith's Defender;

God bless — no harm in blessing — the Pretender;

But who Pretender is, or who is King,

God bless us all — that's quite another thing."

NOTES

1. Once well-known authors of hardback fiction who also wrote Sexton Blake stories included Delano Ames, John G Brandon, Hugh Cleveley, John Creasey, George Dilnot, Berkeley Gray, Victor Gunn, Gerald Verner, and Jack Trevor Story. "Gray" and "Gunn" were the same man, Edwy Searles Brooks, who only turned to adult thriller fiction in middle age.

Several Blake authors were also published in hardback, usually by Wright and Brown or similar houses catering to the circulating libraries, eg Gwyn Evans, Rex Hardinge, Anthony Parsons, and G H Teed.

2. Alfred Edgar, who wrote several Sexton Blake adventures, later became a successful playwright and Hollywood scriptwriter under the name Barre Lyndon. His plays included The Amazing Doctor Clitterhouse and The Man in Half Moon Street about a scientist seeking eternal life.

3. For further information on Sexton Blake, see:

Sexton Blake Wins (J M Dent Classic Thrillers Series 1986), a selection of stories chosen by Jack Adrian;

E S Turner's classic study, Boys Will Be Boys (Michael Joseph, various editions);

Norman Wright and David Ashford, Sexton Blake: A Celebration of the Great Detective (Museum Press, 1994).

© Derek Hinrich