SEXTON BLAKE 1958

by Walter Webb

"Who is Sexton Blake?"

"Who is Sexton Blake?"

Sacrilege? Or just plain ignorance?

Perhaps the question could have been pardoned during the immediate post-war years of rations, restrictions, and frustrations, Sexton Blake, the once-famous Baker Street criminologist, was but a pale shadow of his former self. The war had played havoc with the Sexton Blake Library, and the old-time authors like Gwyn Evans, Anthony Skene, Gilbert Chester, and G. H. Teed were but happy memories.

Sexton Blake still lived, but only just. Stories varied from the mediocre to the utterly bad:1 the old readers were falling off in their hundreds, and the name of Sexton Blake was unknown to the younger generation, whose literary tastes had changed so startlingly since 1939. In a word, Sexton Blake was dying, and the Amalgamated Press, who cannot run their business on sentiment, must have been sorely tempted to finish him off, and bury him.

Providence, in the person of Mr. W. Howard Baker, decreed otherwise. Taking over the editorship of the Library, then at its very lowest ebb, Mr. Baker realised that action, and only drastic action, could save the once-famous detective from total extinction.

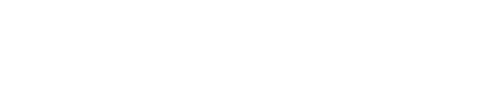

I have not yet been fortunate enough to meet Mr. Baker, but I know that he is not a man of half-measures. The patient, critically ill, needed, not medicine, but a major operation. Dynamism was needed to save Blake, and the new editor possessed that in abundance. The new dynamic editor decided to create a new, dynamic Blake, — and how we hated him at first! Ignorant of the dire distress into which the Library had fallen, we almost cursed the startling changes that were brought about: the changing of the cover, the renting of a suite of offices in Berkeley Square, the engagement

(horrors!) of a beautiful young secretary, Paula Dane, a pretty young typist, Marion Lang, and even a receptionist, Miss Louise Pringle. The great man was now surrounded by three doting females, and the faithful and popular Tinker was cast into almost complete obscurity. Could anything have been more dismaying? To make matters worse, the old authors were discarded, and a completely new and modern team of writers stepped quickly into their shoes. How on earth could these people know our Sexton Blake?

Mr. Baker must have been overwhelmed by letters of criticism, some rude, many, I am sure, abusive. I myself wrote a severe letter criticising the drastic changes, and received a courteous, reasoned reply. Entirely without enthusiasm, I decided to give the new Blake a trial, and how I winced when I read about Paula Dane, Marion Lang, and Miss Pringle!

For sentimental reasons only, I read the yarns month by month, until I suddenly realised that the new editor was playing fair with us older readers. The beloved Tinker came more and more into the scheme of things: Detective Inspector Coutts came back in a small way: Dr. Huxton Rymer, even though a very disappointing Rymer, made a welcome return. I realised that I was beginning to look forward to the first Tuesday in the month. The stories, written by this talented new team, were, on the whole, excellently told, and were full of action, and topical action at that. And, during all this change, Sexton Blake had remained essentially British. More modern in his approach to crime, more up-to-date in his conversation and mannerisms, but definitely a most appealing character.

I decided that I liked this new Blake, and, what is more, I liked the "new-look" of the Library itself. I believe that countless other readers shared my feelings, and my conversion. And now, the rejuvenated Sexton Blake appears to be going from strength to strength, and Mr. Howard Baker's policy has been vindicated without the slightest doubt.

I would call 1958 the year of consolidation for the new Blake. Glancing back, it is interesting to note that the 24 novels were written by no less than nine different authors: five by Jack Trevor Story, four by W. Howard Baker, three each by Arthur Maclean and Peter Saxon, and one solitary contribution by Desmond Reid.2 Most were excellent reading, several were good, and not one of them was bad.

What were the highlights of 1958?

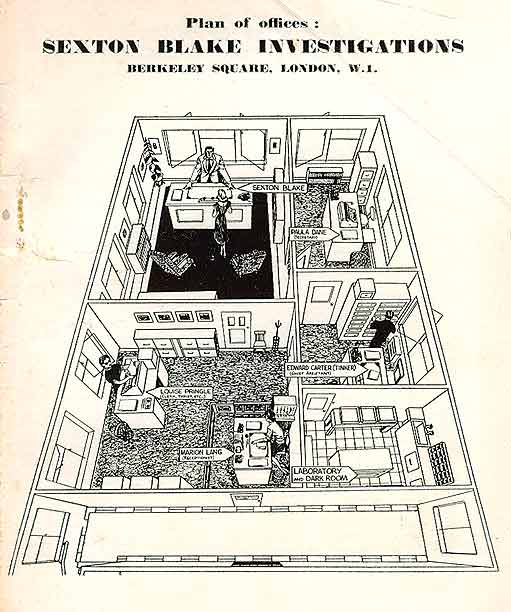

Well, it is only my opinion but I believe that Peter Saxon's "The Sea Tigers" stood out above all others, and was one of the finest Blake yarns ever written. This was indeed an epic, and one of which this talented writer should be justly proud. Incidentally, this story introduced us to a grand new character, — Hazel, the gentle giant, whose greatest hobby was collecting old copies of the Magnet. Saxon's two other efforts, "The Naked Blade", with Blake following a trail of murder from London to a lost city of the Mayas, and "The Voodoo Drum", a thrilling yarn of murder and vice in

Jamaica, made 1958, in my opinion, Saxon's year.

Well, it is only my opinion but I believe that Peter Saxon's "The Sea Tigers" stood out above all others, and was one of the finest Blake yarns ever written. This was indeed an epic, and one of which this talented writer should be justly proud. Incidentally, this story introduced us to a grand new character, — Hazel, the gentle giant, whose greatest hobby was collecting old copies of the Magnet. Saxon's two other efforts, "The Naked Blade", with Blake following a trail of murder from London to a lost city of the Mayas, and "The Voodoo Drum", a thrilling yarn of murder and vice in

Jamaica, made 1958, in my opinion, Saxon's year.

The unorthodox Jack Trevor Story contributed five novels. His flippant, leg-pulling style is not everybody's cup of tea, as I well know, but who can deny the excellence of his work? Perhaps the pick of his stories was "She Ain't Got No Body", a very light-hearted and amusing yarn of loves and hatreds in a picturesque little village in the Thames Valley. Blake even buys a cottage there, he is so entranced by the place. I must confess that I am not exactly enamoured of Story's presentation of Blake, but I also know that he gives much pleasure to countless other readers who enjoy his humorous style.

W. Howard Baker's four novels were well up to his usual high standard, and the quality of his writing cannot be denied. He writes with punch, and he never fails to thrill. I liked particularly his thriller of the French Resistance and the Dieppe Raid, "No Time To Live", in which Louise, the brave, young British agent, distinguished herself. Who would have believed that the courageous Louise, and the quiet, efficient Miss Pringle were one and the same? A nice touch, this! That other gripping yarn of Howard Baker's, "Crime Is My Business", is notable because the newly-released Blake film3 is based on it, and it promises to be a big success with the box-office. Watch out for it, you Blake fans!

I was particularly impressed with Martin Thomas's two stories, "Lady In Distress", and "The Evil Eye". The latter especially was full of suspense and excitement, and was a most entertaining yarn of witchcraft near Loch Lomond. Martin Thomas has a nice touch of the macabre, which always goes down well, and he promises to make a big hit with readers. If he does not become one of the most popular of the modern Blake writers, then I'm no judge of first-rate thrillers.

Edwin Harrison also possesses a most pleasing style, and I thoroughly enjoyed his gripping yarn, "The Fatal Hour", which takes Blake and Paula to Barcelona in order to solve a murder by poisoning in the bull-ring. Arthur Kent's "Stairway to Murder" and "Wake Up Screaming", based on the Norfolk Broads, lacked nothing in interest and excitement, whilst James Stagg's account of murder in a pretty little village in the Cotswolds appealed to me immensely. The title of this was "Crime of Violence", and featured our old favourite, Coutts. Stagg's previous novel, "Murder Down Below", staged in North Devon, was unusual and good in that it portrayed the human side of Blake in his obvious sympathy for the murderer, and such a good story at the beginning of 1958 augured well for the remainder of the year. We have not been disappointed.

Edwin Harrison also possesses a most pleasing style, and I thoroughly enjoyed his gripping yarn, "The Fatal Hour", which takes Blake and Paula to Barcelona in order to solve a murder by poisoning in the bull-ring. Arthur Kent's "Stairway to Murder" and "Wake Up Screaming", based on the Norfolk Broads, lacked nothing in interest and excitement, whilst James Stagg's account of murder in a pretty little village in the Cotswolds appealed to me immensely. The title of this was "Crime of Violence", and featured our old favourite, Coutts. Stagg's previous novel, "Murder Down Below", staged in North Devon, was unusual and good in that it portrayed the human side of Blake in his obvious sympathy for the murderer, and such a good story at the beginning of 1958 augured well for the remainder of the year. We have not been disappointed.

Last, but by no means least, Arthur Maclean is one of the most outstanding of the present Blake team, and can always be relied upon for a good, meaty story, as witness his "Redhead for Danger", featuring Tinker and Coutts, and the Great Chalice of Antioch, and "Final Curtain", in which that popular character, Splash Kirby plays an important part. His latest effort, "The House On The Bay", in which that enigmatic character, Craille, sends Blake on a perilous end-of-war mission to track down Japanese war criminals in the Far East, completes a very fine series of yarns. If 1959 proves as good, we shall have every reason to be satisfied.

To sum up: The Sexton Blake of 1958 is a most attractive character, Tinker has been restored to his rightful place, Paula, Marion, and Miss Pringle are portrayed so sympathetically that most of us have come to accept them, and, indeed, even to like them. And even though the Coutts of today is only a lukewarm reflection of the former ebullient and pugnacious Scotland Yard man, and the homely Mrs. Bardell is seldom, alas, mentioned, we have a lot to be thankful for.

Blake is known and respected throughout the land again, and we are likely to read about and share his thrilling adventures for many years to come.

What more could we ask for?

Mark Hodder's notes:

1. The generation of Blake readers whose early years had been enhanced by the glorious UNION JACK story paper were generally scornful of — or, at least, disappointed with — the tales that appeared in the SEXTON BLAKE LIBRARY from 1935-ish up until the advent of the New Order in 1956. They referred to this period as Blake's "lean years." From the perspective of a modern reader, though, there is a lot to love about the so-called "nadir" of Blake. I prefer to call it his era of "domestic crimes" or "cozy crimes." Out went the colourful (and unrealistic) master crooks and in came little kitchen sink dramas, ordinary people suffering at the hands of petty villains, and a very realistic reflection of life in post-war Britain.

2. When Walter Webb wrote this article, he was unaware that Arthur Maclean, Peter Saxon and Desmond Reid were pseudonyms. The actual count for 1958 is 7 by W. Howard Baker, 5 by Jack Trevor Story, 2 by James Stagg, 2 by Arthur Kent, 2 by Martin Thomas, 2 by Edwin Harrison, 2 by George Paul Mann, 1 by T. C. P. Webb, and 1 by John Purley (with revisions by George Paul Mann).

3. MURDER AT SITE THREE starring Geoffrey Toone as Sexton Blake, Jill Melford as Paula Dane, and Richard Burrell as Tinker. Directed by Francis Searle. Released August 1959.