CURTAIN CALL FOR A FORMER HERO

by Dan O'Neill

For those who remember the old Union Jack or Marvel or Jester, it was, of course, no surprise that the abrupt retirement of John Profumo from public life this year followed so closely the rather more leisurely farewells of Sexton Blake, the world's oldest active detective.

Blake aficionados know that their hero is — or, alas, was — the one man in the world who could possibly have prevented a cabinet scandal of the proportions that brought joy to Fleet Street in June. They knew that Sexton Blake had gone: they knew that for the first time in seventy years the Prime Minister could not hiss to his assembled colleagues "There is only one man who can help us. Send for Sexton Blake."

Blake aficionados know that their hero is — or, alas, was — the one man in the world who could possibly have prevented a cabinet scandal of the proportions that brought joy to Fleet Street in June. They knew that Sexton Blake had gone: they knew that for the first time in seventy years the Prime Minister could not hiss to his assembled colleagues "There is only one man who can help us. Send for Sexton Blake."

Maybe the Cabinet crisis arose because Blake was no longer around to prevent it. More likely though, Blake retired because of the crisis he knew was about to erupt this summer.

The England he had known for so long had disappeared. He could not put his noble talents to work for what he would consider an ignoble cause. In his long and omnipotent career he had walloped Kaiser Wilhelm and saved the Crown Jewels; he had worked for what he had insisted on calling "the Grand Old Flag" in Russia, China and the remoter peaks of the Himalayas. But no longer. There was no place for Sexton Blake in the neon-lit, espresso-flooded England of tawdry clubs, Teddy Boys and Keeler-dealers of the 1960's.

So he slid away with the silent, practiced ease that had, over the years, marked his passing from dacoit's dens, scorpion-crammed cellars and those moor-surrounded mansions where the Family Curse strikes with monotonous regularity.

It was a sad farewell, suitably toasted in a Fleet Street tavern by the writers who had chronicled his later adventures. While they reminisced over their half-pints other writers were translating the memoirs of Christine for public and wide-eyed consumption in the pages of that great family journal, the News of the World.

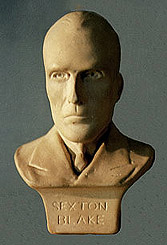

So far, so good — for readers of the old Union Jack or Marvel or, perhaps, the Jester. But it occurs to me that some of you might be wondering who the devil Sexton Blake was. Imagine a fanfare of police hand trumpets blown by all the others from Holmes to Hammer and I'll tell you. Sexton Blake was, for millions, the greatest detective the world has ever known. He was also the detective who lasted longest. He began in the gas-lit London of Oscar Wilde's Yellow Nineties and ended, reluctantly, in what we might call the guilt-lit London of the Scarlet Sixties.

So far, so good — for readers of the old Union Jack or Marvel or, perhaps, the Jester. But it occurs to me that some of you might be wondering who the devil Sexton Blake was. Imagine a fanfare of police hand trumpets blown by all the others from Holmes to Hammer and I'll tell you. Sexton Blake was, for millions, the greatest detective the world has ever known. He was also the detective who lasted longest. He began in the gas-lit London of Oscar Wilde's Yellow Nineties and ended, reluctantly, in what we might call the guilt-lit London of the Scarlet Sixties.

Between the first Blake epic (The Missing Millionaire: the story of a daring detective) and the last (The Last Tiger, in which no one had to be told Blake was a daring detective) he solved approximately ten thousand crimes and had more than three hundred million words written about him by a variety of authors which included Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, Peter Cheyney, John Creasey and Dorothy L. Sayers.

His seldom-routine adventures were translated into a dozen languages ranging from Urdu to Arabic. (God knows what inferiority complexes were inflicted on some of those who spoke those languages.) Sexton Blake was the hero of a batch of movies and it's claimed that the first films to be made under the British Films Quota Act were based on his adventures, beginning as early as 1914. David Farrar is probably the most familiar screen Blake but there were at least two earlier ones, George Curzon and Langhorne Burton. The last cinema-Blake was a steel-eyed hawk called Geoffrey Toone, a name more likely to belong to a villain in one of the vintage adventures.

In any case, for a large number of Britons Blake will always be as real a sleuth as, say, ex-Superintendent Cherrill of the Yard. That very same Cherrill, incidentally, was quoted on the cover of a Blake novelette earlier this year as saying that it was Sexton Blake, "this intrepid hero, who first fired my imagination to become a detective."

Fervent admirers of Blake resent the libel that their hero began life as "the office boys' Sherlock Holmes." Holmes had only been sleuthing for six years himself when Sexton Blake appeared on December 20, 1893, in the Christmas edition of the Halfpenny Marvel.

Fervent admirers of Blake resent the libel that their hero began life as "the office boys' Sherlock Holmes." Holmes had only been sleuthing for six years himself when Sexton Blake appeared on December 20, 1893, in the Christmas edition of the Halfpenny Marvel.

In that one he solved the mystery of The Missing Millionaire, and it was written up by Harry Blythe under the more imposing pseudonym Hal Meredeth. The detective spoke in a style that wouldn't have disgraced a house-master at Dr. Arnold's Rugby, and even Holmes himself must have been impressed by what sounded like his own echo. Holmes, however, always looked like Basil Rathbone; Blake appeared as a plump Victorian complete with high-domed bowler and heavy cane. And he scorned Baker Street, preferring to work from New Inn Chambers.

Like Holmes, Sexton Blake was "one of the new order of detectives." Fascinated butcher boys, gulping over the Marvel, learned that he possessed a highly-cultivated mind which helped support his active courage. His refined, clean-shaven face lent itself readily to any disguise and his mobile features assisted to clinch any facial illusion he wished to produce. That cane, though it might have looked like something Oscar Wilde had left behind at the club, could deal a smart rap across criminal knuckles, too.

On the day of his first case Blake's refined, clean-shaven face looked thoughtful. The client who began Blake's career in print, a Mr. Frank Ellaby, entered the detective's drawing room and, apparently without drawing a breath, took the whole of the Marvel's front page to deliver an enormous monologue aimed at giving the detective and readers what would be known, years later, as "just the facts."

Well of course, the case was solved with such verve that it could only be the beginning. Sexton Blake stalked through the pages of boys' magazines from then on, graduating from such unimposing matters as missing millionaires to the point where pallid prime ministers were constantly tying up the telephone exchanges in their efforts to get "the one man who can help."

And in those gloriously jingoistic days Blake knew how to behave. There is, for example, Blake's marvellous oration to a naval man seeking his help: "I would rather work for nothing for a naval man like yourself, one of the best protectors of our precious flag, the pride of England, then I would take banknotes from those who are careless of the honour of old Britain."

It's an illustration of the country's mood at the time that Blake could say this without a trace of self-consciousness and that the naval man could listen without a blush. That was the stuff to make an office boy's heart swell...

It's an illustration of the country's mood at the time that Blake could say this without a trace of self-consciousness and that the naval man could listen without a blush. That was the stuff to make an office boy's heart swell...

Gradually he built around him a group that featured, therefore, an office boy with whom the readers could identify. For almost seventy years the boy Tinker stayed with his master, progressing, in the end, to assistant and near-partner. Three office boys preceded Tinker but only the first could be remembered. He was a Chinese boy called We-wee. For obvious reasons Blake had to let him go...

In 1904 Blake and Tinker "retired to the country." But he could not for long stay away from a fascinating underworld where the criminal cream (Mr. Mist, the Invisible Man, Dr. Satira and the Black Trinity) were operating opposed only by the talentless hacks of Scotland Yard. By 1915 he was back with his own platform - the Sexton Blake Library. In the first issue the enemy was The Yellow Tiger. In the last issue, 1,652 issues later in June of this year, the title was, ironically, The Last Tiger.

In 1904 Blake and Tinker "retired to the country." But he could not for long stay away from a fascinating underworld where the criminal cream (Mr. Mist, the Invisible Man, Dr. Satira and the Black Trinity) were operating opposed only by the talentless hacks of Scotland Yard. By 1915 he was back with his own platform - the Sexton Blake Library. In the first issue the enemy was The Yellow Tiger. In the last issue, 1,652 issues later in June of this year, the title was, ironically, The Last Tiger.

During those years Blake went through as many facelifts as a movie queen. It was always a problem to stop him from looking dated as times and fashions changed. The egg-shaped sleuth in patent-leather boots and curly-brimmed bowler so suitable for 1905 could hardly compete with the hard-boiled, pistol-packing private eyes of the Sam Spade era. Blake was given periodic alterations — and new clothes — but his philosophy didn't change much and his heroines remained unkissed.

But in the last twenty years he faced his biggest tests — tests unconnected with the cases he could still solve so effortlessly. Readers who had just survived a shocking war knew realism when they saw it and villains like Waldo the Wonder Man or the executive of the Criminals Confederation were emphatically unreal. So Blake worked on the Case of the Conscript Miner or the Yank Who Came Back. There was even one featuring a Missing G.I. Bride.

Blake's diction changed, too. He stopped saying "hist" or "pray" and began to talk like a human being — something he had rarely been guilty of in those early years. They managed to drag the detective into the post-war world and they were able to blend him, physically, anyway, with it. But they could never take the big step, the step which would have given Blake the morals of the world he found himself inhabiting.

It became hard to believe in a detective incapable of kicking a black marketeer in the groin or a beautiful girl in the teeth. In Blake's profession the outlook that had once jerked office boys to attention was not, any longer, a qualification.

Sales sagged. The suave Bond, the brutal Hammer, the men for whom the end justified any means, were easier to relate to for the public.

The last great facelift came in 1957. Although Blake was allowed to retain his overpowering erudition — he knew everything - he didn't stress it too much. Oh, a quick identification of a little-known Asiatic poison could be approved, but the Blake who once wasted his time writing monographs on Finger Print Forgery by the Chromicized Gelatine Method or Speculations on Ballistic Stigmata in Fire-Arms took a back seat. Instead, in 1957, a Blake to rival Bond in all but sex-appetite was created.

The last great facelift came in 1957. Although Blake was allowed to retain his overpowering erudition — he knew everything - he didn't stress it too much. Oh, a quick identification of a little-known Asiatic poison could be approved, but the Blake who once wasted his time writing monographs on Finger Print Forgery by the Chromicized Gelatine Method or Speculations on Ballistic Stigmata in Fire-Arms took a back seat. Instead, in 1957, a Blake to rival Bond in all but sex-appetite was created.

Smooth, sophisticated: that was Blake. And Tinker the office boy was given those Bond attributes which it wouldn't have been wise to graft on to Blake. Tinker became a lady-killer and a figure much easier to accept in a society where fifteen-year-old office boys could spend in a week what their Blake-reading grandfathers had earned in three months.

A gorgeous secretary appeared and old faithfuls longing for Mrs. Bardell, erstwhile housekeeper who spoke like Sary Gamp and kept the muffins coming, shuddered. Paula Dane was blonde and liked art and music. Another hobby that doubtless helped her land the job was small arms shooting. Everyone but Blake realized that Paula loved her boss. But in this respect alone the hawk-like eyes were dim.

This major change in Blake's personality and habits was of sufficient interest in 1957 for London's newspapers to describe it to their readers, most of whom, presumably, were familiar with the detective.

The Daily Mail described W. Howard Baker, a thirty-year-old Irishman, as the "re-decorator" behind Blake's new look. Mr. Baker explained that "this last survivor of the gentlemanly school of Victorian clubland sleuths" had to be overhauled to compete and boost the sale of the forty-thousand word Blake novelettes that appeared every two weeks.

"The whole setup in Baker Street on cosy afternoons with rain pattering against the windows, Blake in his dressing gown, Tinker curled up on the rug and Mrs. Bardell serving up the crumpets belonged to the past," said Mr. Baker and added that while such scenes still put a spell on the tradition-lovers they wouldn't bring in any new customers. A new image was needed.

Blake was given a leaner, more handsome face and despite his 60-odd years of crime-fighting, put "just the right side of 40." He traded his Rolls for a Jaguar or Bentley and the rooms on Baker Street were vacated in favour of a plush office suite in Berkeley Square.

Blake was given a leaner, more handsome face and despite his 60-odd years of crime-fighting, put "just the right side of 40." He traded his Rolls for a Jaguar or Bentley and the rooms on Baker Street were vacated in favour of a plush office suite in Berkeley Square.

But there was one tradition which even the energetic Mr. Baker couldn't shatter. In the course of a long career the detective had fascinated, as the early biographies said, many women. Yet he had never gone beyond gallantly brushing the backs of their hands with his lips. (Once Blake did kiss a villainess called Roxanne but, as she had gassed him with a cunning little pistol, that episode can be discounted.)

So it was no romance for Sexton Blake in 1957. It was, said Mr. Baker, the one thing that couldn't change. Blake had to have "complete control and integrity."

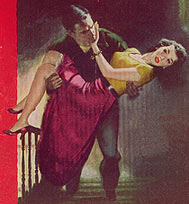

The covers of the books following that change revealed that Blake did, indeed, possess remarkable control. Blondes, brunettes and red-heads, not one of them able to control a shoulder strap, began to appear on the increasingly lurid covers. Only the old readers knew that Blake's control and integrity could hold out. The later readers attracted by the new look would have said that no man could.

They were disappointed. For Blake was no ordinary man. He kept his integrity intact despite his writers' unfortunate habit of throwing him into contact with females beside whom the early adventuresses looked like Tinker. He successfully survived Death and the Little Girl Blue, Requiem for Red-heads and a Dangerous Playmate. He always returned to his office in that implacably virtuous state and Paula Dane waited with love in her eyes that only the ace detective was too full of integrity to miss.

During the last years Blake went to Moscow, Budapest — for the 1956 uprising — and to the Congo at the time of Independence. (And that was an adventure to make Blake blush.) He stalked through post-war London, surviving the rock-and-roll onslaught as neatly as any other danger, and he practised his craft in an atmosphere familiar to his readers. Country housees and moated granges were fine: but how many readers had been to any? Coffee bars, strip joints and pubs were the places to go - and Blake went.

It couldn't last though, and in 1962 the end began its remorseless approach. A minor change in format made the novelettes "pocket-book size" but in spite of a plea to all Blake followers to recruit at least one new reader, the sales slumped alarmingly.

Bright little plugs began to appear on the covers beneath the bosoms. Leslie Charteris hoped that his Saint would still be as full of life as Blake "when he had reached the same staggeringly successful total of concluded cases." Agatha Christie was delighted to see Blake still going strong, "and with such aplomb." Retired detectives were encouraged to tell the world how much Blake had meant to their careers. Rupert Davies, who played Maigret for television, stoutly maintained that Blake had been one of his earliest heroes.

Letters continued to reach publishers from all over the world showing that interest, even in countries where the 1900 Blake would be regarded as an Imperialist, was still high. But it wasn't high enough. Blake could not compete in a world where the criminals were the Peter Rachmans, kings of slum empires — although Blake had once, long ago, fought such a man. Not even cases involving astronauts or possible government scandals could jerk Blake completely into the sixties.

Everyone knew there was a real-life scandal brewing. And it wasn't the sort that Sexton Blake, unsurpassed at recovering stolen cabinet secrets, would like to deal with. There had been facelifts and changes but in 1963 it was clear that Blake, essentially, had not changed at all. Instead the world around him had changed and he could never be part of it. So in June, 1963, he retired, following his last battle against a Japanese army ready, after twenty years on a Pacific island, to conquer the world with a "force field." Only an attempted rape stopped the last adventure from being as naively noble as the first. That was the end.

Everyone knew there was a real-life scandal brewing. And it wasn't the sort that Sexton Blake, unsurpassed at recovering stolen cabinet secrets, would like to deal with. There had been facelifts and changes but in 1963 it was clear that Blake, essentially, had not changed at all. Instead the world around him had changed and he could never be part of it. So in June, 1963, he retired, following his last battle against a Japanese army ready, after twenty years on a Pacific island, to conquer the world with a "force field." Only an attempted rape stopped the last adventure from being as naively noble as the first. That was the end.