THE DARK HEART OF THE GOLDEN AGE

by Mark Hodder

When Harold Twyman became Editor of UNION JACK in 1921, he immediately made an accurate assessment of the magazine's biggest strength: its tendency to take inspiration from actual events. For years, the UJ Sexton Blake writers had used current affairs as the background for their narratives. Anything from the sinking of the Titanic to a cricket test match was fair game. While, in the early days, these tales were often told within the conventions of late-Victorian popular fiction (there was nearly always a 'young couple's love at risk' scenario), they were nevertheless told from a 'ground level' perspective, as if the author had actually witnessed the events (which, in fact, was often the case). This gave the stories an air of 'truth', making it seem as if Sexton Blake was a living person; a part of the readers' world.

When Harold Twyman became Editor of UNION JACK in 1921, he immediately made an accurate assessment of the magazine's biggest strength: its tendency to take inspiration from actual events. For years, the UJ Sexton Blake writers had used current affairs as the background for their narratives. Anything from the sinking of the Titanic to a cricket test match was fair game. While, in the early days, these tales were often told within the conventions of late-Victorian popular fiction (there was nearly always a 'young couple's love at risk' scenario), they were nevertheless told from a 'ground level' perspective, as if the author had actually witnessed the events (which, in fact, was often the case). This gave the stories an air of 'truth', making it seem as if Sexton Blake was a living person; a part of the readers' world.

Twyman demanded more of this and he got it. But something else happened too… something that, taken at face value, seemed to have very little to do with real life: an explosion of super-villains.

Sexton Blake had been meeting extraordinary criminals since 1908 when George Marsden Plummer made his debut. They were few and far between back then but over the ensuing years their number increased. Plummer appeared more and more often; Count Carlac was introduced in 1912, followed by Dr. Huxton Rymer and Wu Ling; 1913 saw the arrival of Professor Kew; 1915, Leon Kestrel; 1916, Dirk Dolland, and so on.

By 1919, all the big names were present and keeping the Baker Street detective very busy indeed. It would be fair to argue that these characters actually brought more dramatic value to the saga than Blake himself. Certainly, their personalities were better defined. Sexton Blake, in individual stories, often had a rather vague persona. It's only after reading a number of tales, taken from different periods in his history, that you begin to gain a full sense of the man. The super-villains, though, leaped fully-fledged from the page almost immediately.

By 1919, all the big names were present and keeping the Baker Street detective very busy indeed. It would be fair to argue that these characters actually brought more dramatic value to the saga than Blake himself. Certainly, their personalities were better defined. Sexton Blake, in individual stories, often had a rather vague persona. It's only after reading a number of tales, taken from different periods in his history, that you begin to gain a full sense of the man. The super-villains, though, leaped fully-fledged from the page almost immediately.

This seems rather strange because, as characters, they were far more complex than Blake, so you'd expect his more straightforward presence to have greater clarity. The super-villains had multifaceted psychological motivations; their behaviour was often confusing and irrational. They were extraordinary people doing extraordinary things ...

So where did they come from and why were they so successful?

There's a clue in the dates. It's no coincidence that the super-villains ushered in Sexton Blake's Golden Age at almost exactly the same time as the First World War ended. The moment you look at the social conditions of the time, it immediately becomes apparent that the likes of Plummer, Zenith, Kestrel and Rymer were metaphors for the psychological experiences of a whole generation of men.

There's a clue in the dates. It's no coincidence that the super-villains ushered in Sexton Blake's Golden Age at almost exactly the same time as the First World War ended. The moment you look at the social conditions of the time, it immediately becomes apparent that the likes of Plummer, Zenith, Kestrel and Rymer were metaphors for the psychological experiences of a whole generation of men.

Troops returning from the front line found themselves in a changed world. The old order had been overturned; social distinctions had blurred; the concept of 'honour', so important to a soldier in previous conflicts, had been battered to extinction by the inhumanity of modern warfare. Veterans, hailed as heroes when they left for the front, now felt shunned. The comradeship they shared under fire was gone. They found it difficult to get work and to re-integrate into the society they had fought to protect; a society now altered beyond recognition by the experience.

It is this sense of alienation and injustice that formed the basis for the Blakeian super-villain. Ex-soldiers were forced to rely on their own resources — and the super-villains did the same.

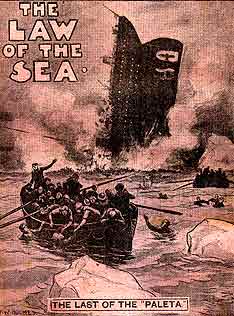

So there is a sense of sadness and exile about these characters. Zenith the Albino is the most obvious example… but it applies to all the others too. Their exclusion from society is contrasted with Sexton Blake's inclusion. Essentially, they are very similar to the detective; possessing (in various degrees depending which villain you examine) great strength, finely-tuned skills, scientific knowledge, mental superiority and/or an unusual ability.

But while Blake's talents are used in defence of the status quo, the super-villains use theirs to try to destabilise it. Why? Because they're trying to create a chink through which they can climb back in. These men are estranged and have turned to crime as the only option left to them. Few of them can be called evil. In many cases, they had a streak of goodness which promised some sort of redemption if only it could be allowed to develop.

Take George Marsden Plummer, for example. He was born a noble; the son of the Earl of Sevenoaks. This marks him as a man of the old pre-war order when British culture was divided into stable classes. People knew their 'place'. But through a quirk of fate, Plummer was born too late to be permitted the annual £60,000 that went with the title. Thus he was forced out of his class and into another; one that had to work for a living.

As an Earl, Plummer would have been looked upon by the lower classes as a man with power. He seeks to emulate that which has been denied him by working his way up through the ranks of Scotland Yard. As a Detective Sergeant, he has the authority to enforce the law — a sort of working class equivalent of an Earl. But he also has access to information about the noble and the wealthy — and this gives him the means for blackmail; the means to get that which should have been rightfully his from the very beginning. Thus we see that Plummer only ever tries to return to what, for him, should have been the natural order of things.

As an Earl, Plummer would have been looked upon by the lower classes as a man with power. He seeks to emulate that which has been denied him by working his way up through the ranks of Scotland Yard. As a Detective Sergeant, he has the authority to enforce the law — a sort of working class equivalent of an Earl. But he also has access to information about the noble and the wealthy — and this gives him the means for blackmail; the means to get that which should have been rightfully his from the very beginning. Thus we see that Plummer only ever tries to return to what, for him, should have been the natural order of things.

Yes, it's true that Plummer appeared six years before the war began. But the social conditions were already in place. Modernisation and the pressures of a new industrialised age were already breaking down the old order. The war may well have been inevitable. The alienation of whole swathes of society certainly was.

For some, re-assimilation was beyond hope. They were the villains who, rather than seeking a way back in, attempted to build an alternative social order in which they could occupy a position equivalent to that which they'd lost. Prince Wu-Ling tried it. Mr Reece tried it. The League of Onion Men tried it. And in post-war Britain, many others tried it too, by raising a Marxist banner and campaigning for a new type of more inclusive society. In post-war Russia, they succeeded and lived to regret it.

For some, re-assimilation was beyond hope. They were the villains who, rather than seeking a way back in, attempted to build an alternative social order in which they could occupy a position equivalent to that which they'd lost. Prince Wu-Ling tried it. Mr Reece tried it. The League of Onion Men tried it. And in post-war Britain, many others tried it too, by raising a Marxist banner and campaigning for a new type of more inclusive society. In post-war Russia, they succeeded and lived to regret it.

The rise of the super-villain in UNION JACK magazine can therefore be seen as a mythological reflection of the times; an exact parallel of the social and psychological challenges faced by a whole generation of men after WWI.

This dark undercurrent fuelled Sexton Blake's finest era, a period of extraordinary adventures, fantastic characters, wonderfully talented authors and an insightful and enthusiastic Editor. The Golden Age lasted about twenty years, fading towards the end of DETECTIVE WEEKLY's lifetime; about the time Adolph Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

Again, there's no coincidence. Europe was re-arming. Fathers who had survived the first conflict knew their sons were about to engage in a second. The disaffected masses were now uniting against a real-life super-villain; a man whose ruthless ambitions and sadistic immorality made Sexton Blake's opponents look like rank amateurs.

Again, there's no coincidence. Europe was re-arming. Fathers who had survived the first conflict knew their sons were about to engage in a second. The disaffected masses were now uniting against a real-life super-villain; a man whose ruthless ambitions and sadistic immorality made Sexton Blake's opponents look like rank amateurs.

As metaphors, they had nothing left to represent; reality had changed, the world had moved on. And the Sexton Blake saga moved on too. Though they continued to make occasional appearances, the age of the super-villain had passed.