THE LIVING IMAGE

by Derek Hinrich

I have never seen any of the silent films of the adventures of Sexton Blake, though I have seen portraits of some of the actors who portrayed him and I believe that some of Mr Langhorne Burton’s performances used to be available for screening on 8mm home projectors but no-one I have known has had them. I have, however, seen the interpretations of all three actors who have played the part since the advent of the sound film.

Of the three, I suppose Geoffrey Toone most closely resembled the portrait of the Blake of his day, if only because pen and ink sketches of him replaced the earlier "official portrait" of the "new look" Blake on the inside covers of the Sexton Blake Library issues of the 3rd or, if you prefer, 4th series after the release of Murder at Site Three based on W Howard Baker’s Crime is My Business (SBL3/408). Unfortunately it is over forty years since I saw this film and I recall little, if anything, of it. I wish some TV channel from which I might record it, would put it on one day, even if only in the small hours of the morning!

Of the three, I suppose Geoffrey Toone most closely resembled the portrait of the Blake of his day, if only because pen and ink sketches of him replaced the earlier "official portrait" of the "new look" Blake on the inside covers of the Sexton Blake Library issues of the 3rd or, if you prefer, 4th series after the release of Murder at Site Three based on W Howard Baker’s Crime is My Business (SBL3/408). Unfortunately it is over forty years since I saw this film and I recall little, if anything, of it. I wish some TV channel from which I might record it, would put it on one day, even if only in the small hours of the morning!

The earliest of the three to play Blake, George Curzon, did so three times. One of these, Sexton Blake and the Hooded Terror, based on "Pierre Quiroule’s" Mystery of No 13 Caversham Square (SBL2/569) has been shown on Channel 4 several times and is preserved in the National Film Archive. Curzon’s Blake is brisk, alert, and dapper. He gives an accomplished performance but he does not closely resemble Eric Parker’s definitive portraits of the Blake of the Golden Age. The film is a jolly little thriller with Blake engaged in a desperate, non-stop, no holds barred struggle with an international criminal conspiracy called the Black Quorum, led by a mysterious arch-villain called the Snake. The actor cast as Tinker is saddled with some rather excruciating "humour" in that curious tradition of "B" pictures, that a detective’s assistant must be a bonehead to inject a little light relief into the story. Quiroule’s tale is modified to enlarge the villain’s part (he only appears briefly in the latter part of the novel) to give Tod Slaughter something to get his teeth into. There is not much mystery about the identity of the master criminal (well with Tod Slaughter in the cast who do you think it’s likely to be?), and there is one rather inconsequential scene where the villain and his henchmen sit round a table talking for some minutes before putting on their hoods a-la the Ku Klux Klan. The sequence in the gambling room is, however, ingenious and reminiscent of some of the bizarre touches in the later television series, The Avengers.

As the story is adapted from a novel by Pierre Quiroule, it is inevitable that Granite Grant, the King’s Spy, should appear in it. So he does, in the person of David Farrar in his first screen role and if Tod Slaughter’s part is written up, so the King’s Spy’s is written down and he does not reappear, as in the book, after the first desperate moments. Never mind, for Farrar’s turn was to come.

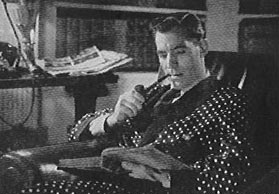

In 1944 and 1945 Farrar played Sexton Blake in his first two starring roles in a pair of films, Meet Sexton Blake and The Echo Murders. Like Blake’s previous appearances, these were second features.

In 1944 and 1945 Farrar played Sexton Blake in his first two starring roles in a pair of films, Meet Sexton Blake and The Echo Murders. Like Blake’s previous appearances, these were second features.

Now none of the films I have mentioned are available on video release in this country but oddly enough these two — it must be said — fairly obscure films have been released on tape in the USA, and I have been fortunate enough to view them on my current recorder which seems to be able to play American tapes reasonably.

Before watching them I consulted David Quinlan’s British Sound Films The Studio Years 1928 – 1950. From this I learnt that Meet Sexton Blake and The Echo Murders were “from characters by Harry Blyth”, which seemed to be going back a bit! I knew that the Sexton Blake Index identified The Echo Murders as being taken from The Terror of Tregarwith by John Silvester (SBL 3/47) but no attribution was given in the Index for Meet Sexton Blake. Then I saw in Quinlan that the cast of characters included Superintendent Venner, so I realised that the film must be taken from something by Anthony Parsons. I soon found that it was based on The Mystery of the Free Frenchman (SBL 2/741). The film follows the book fairly closely with the exception that one of the subsidiary villains is an agent of the OGPU, an earlier name for the KGB (though I’m not sure that this was the one in use in 1941: the initials, and whatever they stood for, changed several times over the years). As the Soviet Union was our gallant ally by the time the film was made, aspersions of this type could not be countenanced. The plot was a murky business (so was the film, quite literally, for the first ten minutes or so, which took place at night by the Thames in the black-out in London during an air-raid) involving dealing and double-dealing and enemy agents after the formula for a new alloy to be used in aircraft construction, and the machinations of that stand-by of the British thriller in the inter war years, the international arms magnate (shades of Sir Basil Zaharoff!) making a rather late in the day appearance in such a story: there were far more real and potent villains abroad. One puzzle I found in the book was that several of the characters flew direct from Switzerland to London in 1941. Would the Luftwaffe have allowed this?

The Echo Murders also adhered closely to its original, The Terror of Tregarwith, with one extraordinary exception. The character of Tinker, who has a substantial part to play in the book, is entirely omitted from the adaptation! Not quite Hamlet without the prince, perhaps, but certainly a loss. The novel was concerned with a fiendish plot by German spies and fifth columnists to establish a secret advanced base or beach-head, for a German invasion of this country using a Cornish tin mine whose workings connected with sea-caves, but first they have to close the tin mine down and much dirty work is necessary to achieve that first step. There is also a convoluted melodramatic subplot concerned with blackmail, a forced marriage, and the ownership of the mine itself. The reader certainly got full value for his seven pence halfpenny in 1941.

Both films were strenuous spy thrillers with rather florid plots and a reasonable competence for the first half of the old-fashioned weekly double-billed programme of the 'Forties, with casts drawn from the staple list of character actors and actresses that regularly provided the support in British films of the time. They were both directed by John Harlow, who was responsible for a number of enjoyable but unmemorable melodramas in that decade.

David Farrar made a very acceptable Blake, rather more virile than either of the other two and I think he would almost certainly be my choice of the three for the most suitable personification of Our Hero, though I would like to have another look at Geoffrey Toone before giving a final opinion on that point. Toone must have been the oldest of the three when he played the part: Murder at Site Three was made in 1958 and I remember him as an army or territorial officer in the 1939 film version of Guy Dumaurier’s hoary old war-scare play about an invasion of Britain, An Englishman’s Home.

Farrar, however, was thirty-six at the time, just the right age by a consensus of the Golden Age authors and his features were suitably aquiline in the manner approved by Parker, whose portraits he closely resembled (though his hair was a shade wavy). He wore a polka-dot dressing gown, however, which looked rather more Noel Coward than Baker Street, and he tended to smoke a Ropp cherrywood pipe, which is rather more Holmes (who smoked clays, briars, and cherrywoods at different times — when he was not indulging in cigars and cigarettes) than Blake (who remained steadily faithful to briars — when he was not indulging in cigars and cigarettes). How heroically these heroes smoked in days gone by!

© Derek Hinrich