SEXTON BLAKE IN THE PENNY PICTORIAL

by Walter Webb

They were days of fear, suspicion, and unrest. The swords of a major European Power were rattling ominously in their scabbards. The King of England had but two years to live, and, in a few months, Jack Johnson would become the World's Heavyweight Boxing Champion by beating Tommy Burns in the 14th round at Sydney Stadium, Australia, in one of the bitterest battles in the history of the ring. Not yet had films emerged from their crude state of silent animation; nor yet had the hem of the feminine skirt begun its gradual ascent to regions which were to afford the imagination of man the minimum effort. It was during this period that Hamilton Edwards, editor of PENNY PICTORIAL, decided to publish a series of short Sexton Blake stories of some 5,000 words, or so, in length.

They were days of fear, suspicion, and unrest. The swords of a major European Power were rattling ominously in their scabbards. The King of England had but two years to live, and, in a few months, Jack Johnson would become the World's Heavyweight Boxing Champion by beating Tommy Burns in the 14th round at Sydney Stadium, Australia, in one of the bitterest battles in the history of the ring. Not yet had films emerged from their crude state of silent animation; nor yet had the hem of the feminine skirt begun its gradual ascent to regions which were to afford the imagination of man the minimum effort. It was during this period that Hamilton Edwards, editor of PENNY PICTORIAL, decided to publish a series of short Sexton Blake stories of some 5,000 words, or so, in length.

It was a strange world into which Blake found himself transported. For there was no Tinker. There was no Pedro. No Mrs. Bardell. Not even Baker Street. This presentation of a very lonely figure carrying on his profession in rented rooms in the heart of a big city gave a depressing picture of Blake, even though, on occasions, the gloom was dispersed somewhat by the introduction of a character named Bathurst, and a most presentable belle of Edwardian society named Lady Marjorie Maxwell. Bathurst was described as a friend, and seemed to be connected with a newspaper, whilst the Lady Molly had decided views of depriving Blake of his avowed bachelorhood. A commanding manner, an imperiously beckoning finger, sometimes made Blake appear something of a weakling as he bowed to her wishes, but by no means did her ladyship get everything her own way with him.

When these stories were published they were said to be quite new and up-to-date. Blake, having been ordered to rest by his doctors, has temporarily forsaken Baker Street, and is living during the period of these episodes in a quiet little house in Surbiton, amusing himself by flower culture, the cottage having been lent to him by an old friend, a Mr. Dove, a retired official from Scotland Yard, whilst that individual was away on the Continent.

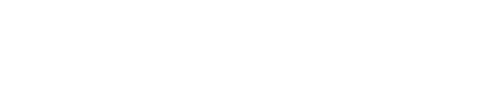

The first story in the series was called "Missing!" and the opening chapter showed Blake, pruning-knife in hand, busy with his roses in the front garden. Why the author chose to give the house the name of Aston Villa would have been obvious to any reader of that period, for the famous club were going great guns in both cup and league at that time. Inevitably, the telephone-bell rang, and Blake, expecting the worst, passed out of the sunlight into the hall to answer its summons. Naturally, it was Scotland Yard at the other end, and so began Blake's first case in his new surroundings. Soon he forsook his rural surroundings to rent rooms in the centre of the City.

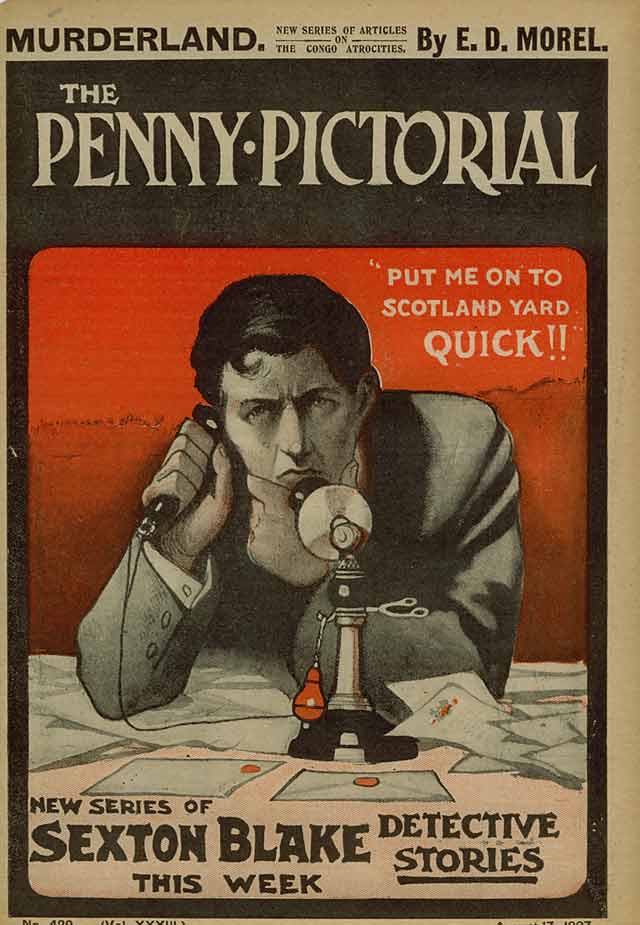

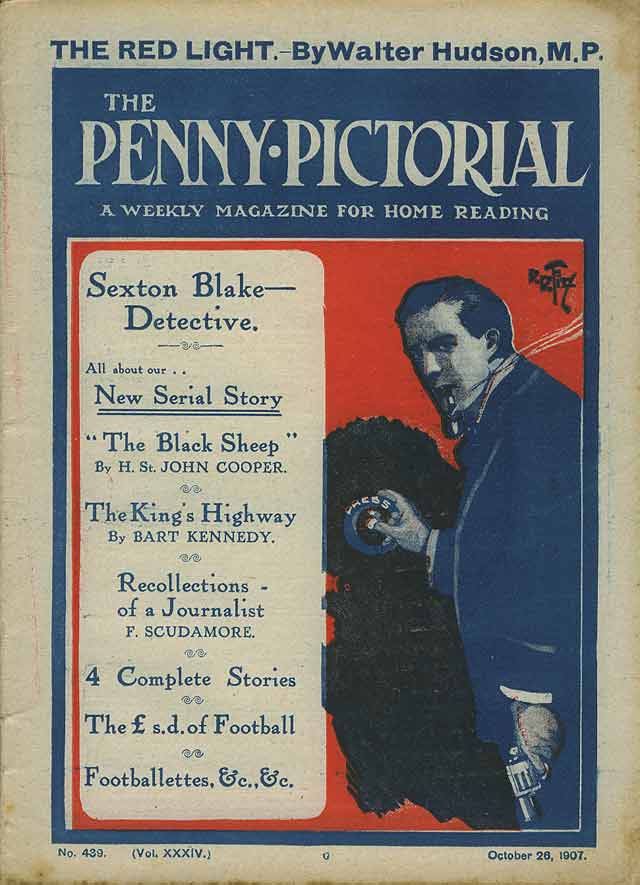

The stories were a mixed bag, with the good outnumbering the bad, and the indifferent outscoring both. Only on the rare occasion was an attempt made to run a series on the lines of those in the UNION JACK. Then, commencing 6th November, 1909, and carrying on until Christmas, came an unbroken run of eight stories featuring Marston Hume, a criminal lawyer, who, throwing up his practice, joined the ranks of those he formerly defended so skilfully. He was a completely bad hat was Marston Hume, sporting a monocle, but bereft of any sporting qualities of any kind. In Blake's view, even imprisonment was too good for him, and it gave the detective much inward satisfaction to bring the master-criminal to his knees and ruin him completely. This was a good series, in which Blake was helped in his campaign against Hume by Bathurst and Lady Molly.

The stories were a mixed bag, with the good outnumbering the bad, and the indifferent outscoring both. Only on the rare occasion was an attempt made to run a series on the lines of those in the UNION JACK. Then, commencing 6th November, 1909, and carrying on until Christmas, came an unbroken run of eight stories featuring Marston Hume, a criminal lawyer, who, throwing up his practice, joined the ranks of those he formerly defended so skilfully. He was a completely bad hat was Marston Hume, sporting a monocle, but bereft of any sporting qualities of any kind. In Blake's view, even imprisonment was too good for him, and it gave the detective much inward satisfaction to bring the master-criminal to his knees and ruin him completely. This was a good series, in which Blake was helped in his campaign against Hume by Bathurst and Lady Molly.

The origin of these stories is somewhat problematical, for in their brevity, they did not lend themselves so easy of identification as did the longer efforts in the UJ. But, as a result of much research, I am confident that the man who wrote nearly all the stories over a period of four years contributed regularly to ANSWERS, PENNY PICTORIAL and many other adult papers run by the Amalgamated Press. He was Cecil Hayter, and on competion of the Sexton Blake series he began another, this time introducing his own detective, Major Derwent Duff, and his Chinese factotum, Chin-Chin.

It is difficult to pin-point the other writers who were called on to help Hayter when he was unavailable. The controversial Michael Storm was certainly one, and brought one of his own characters — Rupert Forbes — into one of the stories, and I feel certain that it was his hand that conceived both Marcus Hume and Lady Molly. Among the other writers who may have contributed the odd story were Stacey Blake, Sidney Gowing, T. C. Bridges, A. C. Murray, Henry St. John Cooper and Dr. J. W. Staniforth. They were all regular PENNY PICTORIAL contributors of that period.

There is a puzzling aspect about the Marcus Hume stories. The last three were certainly written by Hayter, but the preceding five were in a far more leisurely strain to the latter's usually racy style. This was the time of Storm's now famous disappearance from the Street of Ink, so it may well be that with him having left the Marcus Hume series hanging in the air, so to speak, Hayter was left with the job of finishing them off.

The alleged Blake stories by Henry St. John Cooper are still undiscovered, but "The Case of Squire Falconer," published in No. 495 has something of his style of narration about it. Hitherto, Cooper's only known reference to Blake was in a book published in hard covers by Sampson Low in the twenties, when he referred to Blake twice in a crime and mystery novel, entitled "The Red Veil."

Of the other writers who were commissioned, one introduced a man named Simmons, who filled the role of Blake's manservant. Another, a little more specific, gave Blake as having chambers in Messenger Square, wherever that thoroughfare may have been, and of possessing a bungalow at Shorebridge. Of the artists, Leonard Shields illustrated the early stories, but he soon gave way to R. J. Macdonald, which gave quite a strong MAGNET and GEM flavour to the proceedings. Thereafter, Mac did nearly all the drawings, with Harry Lane and J. Louis Smythe contributing a set here and there.

Of the other writers who were commissioned, one introduced a man named Simmons, who filled the role of Blake's manservant. Another, a little more specific, gave Blake as having chambers in Messenger Square, wherever that thoroughfare may have been, and of possessing a bungalow at Shorebridge. Of the artists, Leonard Shields illustrated the early stories, but he soon gave way to R. J. Macdonald, which gave quite a strong MAGNET and GEM flavour to the proceedings. Thereafter, Mac did nearly all the drawings, with Harry Lane and J. Louis Smythe contributing a set here and there.

To conclude, In view of their absence from the SEXTON BLAKE CATALOGUE (this was published by THE SEXTON BLAKE CIRCLE in the late 'fifties — Ed.), the question of whether these stories were of sufficient importance as to have been included arises. Personally, I think they should have been, particularly in view of the fact that much abbreviated versions of early UJ stories reprinted in the POPULAR were considered important enough to be listed. After all, these were original stories, and ran non-stop for four years, which proves that they must have been very popular with the readers of that generation, and should a revised edition of the SBC be contemplated in the future, I think they are worthy of inclusion.*

* They are, of course, included in the BLAKIANA bibliography.