THE WARM HEART OF THE LEAN YEARS

by Mark Hodder

Sexton Blake's Golden Age lasted from about 1920 to the early forties. The shine began to wear off after editorial disagreements caused a loss of direction at DETECTIVE WEEKLY. In 1936, Blake was reduced to a mere twelve-part series in the magazine. The following year, he only appeared in two issues. He was then given full-time residence again but, by 1940, paper shortages spelled the end for the magazine. From that point on the Sexton Blake Library, by then in its twenty-fifth year, became the main source of new stories.

Sexton Blake's Golden Age lasted from about 1920 to the early forties. The shine began to wear off after editorial disagreements caused a loss of direction at DETECTIVE WEEKLY. In 1936, Blake was reduced to a mere twelve-part series in the magazine. The following year, he only appeared in two issues. He was then given full-time residence again but, by 1940, paper shortages spelled the end for the magazine. From that point on the Sexton Blake Library, by then in its twenty-fifth year, became the main source of new stories.

Its editor, Leonard H. Pratt, was in a difficult position. As well as the paper shortage, there were far fewer contributing authors; many were on war service and some of the best known writers had passed away. Nevertheless, Pratt was successful in keeping Blake on the bookshelves throughout the war years and up to his retirement in 1955.

For many readers, though, despite Leonard Pratt's efforts, the forties (particularly the late forties) and early fifties are often regarded as a fairly lean period in Blake's long history. The detective spent far less time globetrotting and fighting exotic super-villains and, instead, seemed to be stuck in the parochial world of Little England, solving 'small' crimes and doing occasional work to aid the war effort.

In THE SEXTON BLAKE FILE (published in THE SATURDAY BOOK, Hutchinson 1946), Reginald Cox quotes from a letter sent to him by an enthusiast:

'I expect you'll agree with me that the vintage years were 1922 (approximately) to 1933 - the days when the stories were being written by Gwyn Evans, G.H. Teed, Hylton Gregory, Robert Murray, Anthony Skene and Lewis Jackson at his best. Evans, Teed and Murray are dead, unfortunately, and in my opinion Jackson isn't as good as he was in the days when he created the Nigel Blake, Olga Nasmyth, and Leon Kestrel series: they were some of the best that ever appeared. The so-called realism of the present policy means that stories are about some good people living in a cottage — part of the swing to the Left, I suppose!...'

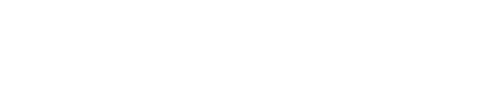

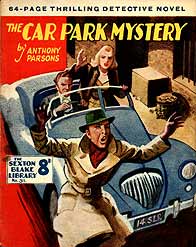

Obviously it was felt that the Blake of the period was too far removed from the glories of the UNION JACK days; less rewarding and rather too pedestrian. Certainly, titles such as THE CAR-PARK MYSTERY and THE SCRAP METAL MYSTERY don't appear to promise much.

But on closer inspection and from the perspective of the 21st century, there is much to admire about the so-called 'Lean Years'. For a start, they provide a fantastic insight into life in Britain during the bleak war and post-war era.

First, we should consider why there was a change of emphasis in the stories; why the focus shifted away from the extraordinary to the mundane. The authors were responding to a grim situation: the world had been permanently altered by the ambitions of Adolph Hitler and the idea of a powerful individual with villainous motivations didn't seem romantic any more. Sexton Blake writers now knew that, in reality, super-villains were the cause of immense suffering and destruction. Unsurprisingly, they lost their appetite for that particular type of enemy.

First, we should consider why there was a change of emphasis in the stories; why the focus shifted away from the extraordinary to the mundane. The authors were responding to a grim situation: the world had been permanently altered by the ambitions of Adolph Hitler and the idea of a powerful individual with villainous motivations didn't seem romantic any more. Sexton Blake writers now knew that, in reality, super-villains were the cause of immense suffering and destruction. Unsurprisingly, they lost their appetite for that particular type of enemy.

The super-villains had symbolised a cultural shift that happened before and during the First World War. Industrialisation and conflict caused a whole swathe of society to become dispossessed. This sense of alienation gave rise to the likes of Zenith, Kestrel, Rymer and co.

But the Second World War drew people back together in a common cause. What's more, the conflict wasn't restricted to the armed forces. For the first time in history, civilians were targeted by the enemy. From this, a great sense of 'community' developed. Many people old enough to remember it still look back fondly on that camaraderie: the wartime spirit. Social barriers fell and the personal trials and challenges previously kept behind closed doors now entered the public arena to be shared by all.

But the Second World War drew people back together in a common cause. What's more, the conflict wasn't restricted to the armed forces. For the first time in history, civilians were targeted by the enemy. From this, a great sense of 'community' developed. Many people old enough to remember it still look back fondly on that camaraderie: the wartime spirit. Social barriers fell and the personal trials and challenges previously kept behind closed doors now entered the public arena to be shared by all.

There was, in consequence, the development of a greater awareness of the problems people had in common; the effects of poverty, the struggle for a better way of life; the things that drove people to crime and the effect of crime on its victims; the hopes and dreams, nobility and small-mindedness of ordinary men and women.

Against this background, authors began to draw on real day-to-day experiences for inspiration; the things that affected the lives of the common populace. In some senses, it could be thought of as a 'comfort zone', in that the misdeeds committed at this level could be understood whereas the crimes of the Nazis were simply inconceivable. Hence we find Sexton Blake confronting petty thieves instead of criminal masterminds; defending the community rather than less comprehensible ideals such as 'honour' (a concept that was killed in WW1 and had no place in WW2).

It should also be noted that this period of history marked the affirmation of Britain's relatively new middle classes as the country's biggest social force. The First World War had all but destroyed the ruling gentry and country peasants. Now, at least in theory, everyone was equal and they all had the same opportunities. As the Sexton Blake stories clearly illustrate, this gave rise to immense frustrations. In the past, people knew their place. The upper classes didn't need to better themselves; the working classes had no chance to do so. But when, suddenly, a rise in status is hypothetically possible, anything that holds you back becomes a source of annoyance and angst. This is as true today as it was during the forties and fifties.

It should also be noted that this period of history marked the affirmation of Britain's relatively new middle classes as the country's biggest social force. The First World War had all but destroyed the ruling gentry and country peasants. Now, at least in theory, everyone was equal and they all had the same opportunities. As the Sexton Blake stories clearly illustrate, this gave rise to immense frustrations. In the past, people knew their place. The upper classes didn't need to better themselves; the working classes had no chance to do so. But when, suddenly, a rise in status is hypothetically possible, anything that holds you back becomes a source of annoyance and angst. This is as true today as it was during the forties and fifties.

So in the stories of the 'Lean Years' we are presented with many examples of people who think they are more important that they actually are — people who believe they have already achieved a rise in status by virtue of the fact that the opportunity is there, even though, in reality, they have been too cowardly, stupid, lazy or misguided to actually achieve anything.

All of this was meticulously recorded in the Sexton Blake Library by a relatively small but very talented band of authors. The minutiae is there; the intricacies of a society battered near to death by five years of vicious warfare and now finding its feet again; a once grand empire reduced to rubble but filled with individuals who still strive for grandeur and recognition; a country of delusions and ghosts; of trivialities and pomposity, opportunity and optimism.

All of this was meticulously recorded in the Sexton Blake Library by a relatively small but very talented band of authors. The minutiae is there; the intricacies of a society battered near to death by five years of vicious warfare and now finding its feet again; a once grand empire reduced to rubble but filled with individuals who still strive for grandeur and recognition; a country of delusions and ghosts; of trivialities and pomposity, opportunity and optimism.

The stories often feature people who are profoundly insecure and yet strangely compelling. Self-doubting teenage thugs, overbearing shopkeepers, incompetent swindlers, star-struck good-time girls and petty hoodlums; the characters beguile with their acutely observed flaws and unrealistic expectations. They feel authentic because they are small; noteworthy because they are insignificant. They feel like real people.

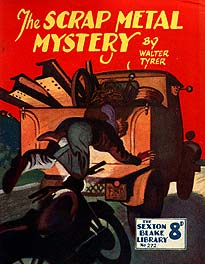

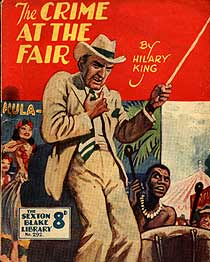

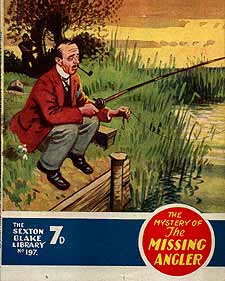

The Blake of the Golden Years would seem out of place in the midst of this crowd. He wouldn't be credible. So the Baker Street detective is somewhat toned down; more ordinary. He's not above investigating the pettiest misdemeanour in the most commonplace of locations: THE CRIME AT THE FAIR or THE RIDDLE AT THE NIGHT GARAGE; THE MYSTERY OF THE MISSING ANGLER or THE CASE OF THE COUNCIL SWINDLE. And while, in the overall scheme of things, these might not be his most memorable adventures, they do make rewarding reading providing you adjust your focus to the period.

There's great warmth about these glimpses into our not too distant past. Depending on your generation, you either remember those decades or you can touch them via your parents or grandparents. So there's an ingredient of nostalgia for things that have only just passed into history, including elements of the English language: "How's it going, old chum?" Nobody says that these days, unless they're of a certain age or living in one of those strangely self-contained pockets of old England which still exist in London's East End. The realism of the dialogue is one of the outstanding characteristics of the stories from this period. They are packed with archaic expressions and utterances, delivering a vivid snapshot of social history surpassing anything a dry text book can offer.

The overall impression is one of Sexton Blake moving through a bona fide living breathing world. It's true that he's often eclipsed by it (in many cases receiving less attention than non-regular characters), but that doesn't detract from the strength of these tales.

So I disagree with those who refer to this stage of the Blake saga as a period of decline. Rather, I would call it an era marked by greater introversion, with authors looking inwards at their culture rather than allowing their imaginations to expand outwards. It was a time when ideals and romance were replaced by facts and realities. It may not be golden but it certainly isn't lacking in riches.