CONAN DOYLE AND SEXTON BLAKE FOR THE DEFENCE

by Derek Hinrich

One evening in May I watched a BBC television programme about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's investigations into two gross miscarriages of justice: the Edalji Case, and that of Oscar Slater. Whilst Sir Arthur's championing of Mr George Edalji in the Great Wyrley horse-maiming case and of Oscar Slater in the still-unresolved Gilchrist murder are well known to his admirers, they are probably not aware of the efforts of Mr Sexton Blake on behalf of Oscar Slater, or rather, I should say, on behalf of Otto Slade.

One evening in May I watched a BBC television programme about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's investigations into two gross miscarriages of justice: the Edalji Case, and that of Oscar Slater. Whilst Sir Arthur's championing of Mr George Edalji in the Great Wyrley horse-maiming case and of Oscar Slater in the still-unresolved Gilchrist murder are well known to his admirers, they are probably not aware of the efforts of Mr Sexton Blake on behalf of Oscar Slater, or rather, I should say, on behalf of Otto Slade.

Miss Marion Gilchrist, an 83 year-old spinster was brutally murdered in her first-floor flat at 15 Queen's Terrace, Glasgow, on the evening of 21st December, 1908, in the ten minutes or so between her maid going out for an evening paper and returning with it. A neighbour, Mr Arthur Adams, who occupied the flat beneath Miss Gilchrist's, heard noises from her flat and, as previously promised to the nervous old lady, went to investigate. He knocked but got no response and returned to his flat but on hearing further disturbance he went upstairs again. As he stood on the landing, Miss Gilchrist's maid returned. She unlocked the door and together they entered the flat. As they did so a man walked out of the flat and then slipped quietly downstairs and away. The maid, who appeared to know the man, let him pass, a few minutes later they found Miss Gilchrist brutally murdered.

The Glasgow police were not without worthwhile leads to follow but they wilfully sidetracked their investigation on the thinnest possible grounds to pursue a shady German pimp named Oscar Slater. After his extradition from the USA, they succeeded in obtaining a conviction against him for the murder. He was sentenced to death but received a last-minute reprieve. The case against him and his conviction was widely seen as a travesty of justice and an intermittent but vigorous campaign for the re-opening of the case soon began. Conan Doyle took up the cudgels on Slater's behalf in 1912 but it was not until 1927 after prolonged agitation by Conan Doyle and other parties that Slater was released and £6000 compensation grudgingly paid to him.

I have given the barest of bare descriptions of this case. A full account may be found in Peter Costello's Conan Doyle Detective which I have had the pleasure of reading since watching the television programme in May (and on which some of that programme was based). In his book Mr Costello reveals for the first time the name of the person whom Conan Doyle suspected of being involved in the murder together with reasons why Mr Costello believes the Scottish establishment of the day closed ranks to protect him.

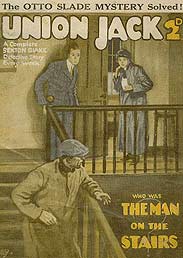

After seeing the programme, however, I turned to my collection of Union Jacks — "Sexton Blake's Own Paper" — and in particular to the issue of September 22nd 1928 which contained a story I had not read hitherto, by Gwyn Evans entitled, WHO WAS THE MAN ON THE STAIRS?

Gwyn Evans' stories were amongst the most popular contributions to the saga of the Other Great Baker Street Detective during his golden age in the 'twenties and 'thirties of the last century. Evans was the son of a Welsh Methodist clergyman and was the subject of a strict and puritanical upbringing. In response he became a mercurial bohemian type who appears at times to have worked to drink. Money ran through his fingers like water. He was possessed of a vivid and fertile imagination which provided him with brilliant plot devices for his fiction, but he was careless and slapdash in execution. His short stories are his best work: with novels he tended to lose interest or patience as the book progressed. Over two hundred authors contributed to the saga of Sexton Blake and so, one might say, there were many Blakes. Gwyn Evans' Blake was the most Holmesian of them.

For instance, a little earlier that same year in a story entitled POISON, set in rural Essex, Blake observes to his assistant Tinker, "You're apt to be too romantic, young 'un. While admitting the beauty of this scene, I don't agree that the country's quite so idyllic as it looks. I have often thought that there are darker deeds committed by evil men in lovely cottages and remote farms than even in a Limehouse slum. Think of the opportunities for cruelty and torture unchecked by police surveillance a man has in the country. I have long held that there are far darker mysteries and unsuspected crimes in a remote village than in a large town…" Sherlock Holmes, musing on a similar theme in THE COPPER BEECHES ("You look at these scattered houses and you are impressed by their beauty. I look at them, and the only thought which comes to me is a feeling of their isolation, and of the impunity with which crime may be committed there ... It is my belief, Watson, founded upon my experience that the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.") would have been at one with him.

Evans' Blake when confronted with a problem had a propensity to don an old red dressing gown, curl up in his favourite "saddlebag" armchair, and smoke quantities of pipe tobacco. In a most ingenious story in 1932 he solved an abstruse mystery by observing the depth that parsley had sunk into butter upon a summer's day (how this compared to Holmes's solution of the "dreadful business of the Abernetty family" from a similar circumstance we shall never know since Watson never told us). I like to think that this tale was conceived as a tribute to Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes.

WHO WAS THE MAN ON THE STAIRS? Is a story in two parts. The first deals with the murder in Edinburgh in 1908 of an elderly lady, Miss Susan Gilbertson, and the subsequent wrongful conviction for the crime on dubious evidence of a man named Otto Slade whose sentence of death is commuted to life imprisonment at the last moment. Apart from the change of venue from Glasgow to Edinburgh; the minimal changes in the names of the participants; and a touch of fiction to enable the plot to develop, this first part is virtually a straightforward account of the Gilchrist murder.

WHO WAS THE MAN ON THE STAIRS? Is a story in two parts. The first deals with the murder in Edinburgh in 1908 of an elderly lady, Miss Susan Gilbertson, and the subsequent wrongful conviction for the crime on dubious evidence of a man named Otto Slade whose sentence of death is commuted to life imprisonment at the last moment. Apart from the change of venue from Glasgow to Edinburgh; the minimal changes in the names of the participants; and a touch of fiction to enable the plot to develop, this first part is virtually a straightforward account of the Gilchrist murder.

The second is set twenty years later and begins with a press baron, Lord Faversham, commissioning Sexton Blake to conduct a fresh investigation of the Gilbertson murder as part of a campaign being run by his papers following Otto Slade's release on completion of his sentence.

Sexton Blake accomplishes his task after some rather melodramatic events, including an attempt upon his life by the real murderer who is presently revealed to the public (though we have been privy to his secret since Part One) as Dr John Bleakman, the son of the judge who presided at Slade's trial, and who as a ne'er-do-well medical student, had been the boy friend of Miss Gilbertson's maid who had recognised him as he passed her on the night of the murder. He had hitherto bought her silence by threatening to denounce her as his accessory before the fact if he was taken.

Following Blake's investigations an appeal is allowed and he denounces Bleakman in open court. Bleakman then commits suicide with potassium cyanide in the public gallery.

WHO WAS THE MAN ON THE STAIRS is a neat little attempt to extract a story from the day's headlines. I also wonder if it is anything of a roman à clef. The name of Conan Doyle's suspect was never mentioned until Mr Costello's book was published in 1991 as The Real World of Sherlock Holmes (I have an American paperback edition with a slightly different title as I indicated earlier). The suspect was a well-connected doctor who, although not related, was loosely referred to as Miss Gilchrist's nephew. His name was Francis James Charteris.

I read somewhere once that many foreign correspondents and other journalists take to spy and other fiction to tell, at least in part, stories and events they cannot publish as fact. Was there anything of this about Gwyn Evans' tale, or was the suggestion of a well-connected doctor just a lucky guess?