NUMEROUS VILLAINS

by Derek Hinrich

Amongst the great serial villains whom Sexton Blake encountered in his hey-day, only the hydra-headed and octopus-tentacled Criminals’ Confederation, was treated as an organisation. Prince Wu Ling of the Society of the Yellow Beetle and, to a lesser extent, Leon Kestrel despite his Syndicate, were treated as predominantly single adversaries. Zenith the Albino, George Marsden Plummer, Huxton Rymer, and the rest, may have had the occasional accomplice but generally were also seen as individuals.

Yet Blake encountered many gangs and conspiracies in his time. Even in his very earliest cases in the eighteen-nineties he encountered such bodies as ‘The Red Lights of London’, ‘The Assassins of the Seine’, and the ‘Terrible Three’ (one of whom apparently had the dangerous and surely risky habit of walking about with one mandarin-like fingernail dipped in venom, ready to scratch an enemy: fortunately Sexton Blake habitually carried a stick of lunar caustic which he used like a styptic pencil).

Yet Blake encountered many gangs and conspiracies in his time. Even in his very earliest cases in the eighteen-nineties he encountered such bodies as ‘The Red Lights of London’, ‘The Assassins of the Seine’, and the ‘Terrible Three’ (one of whom apparently had the dangerous and surely risky habit of walking about with one mandarin-like fingernail dipped in venom, ready to scratch an enemy: fortunately Sexton Blake habitually carried a stick of lunar caustic which he used like a styptic pencil).

Later, Blake, when almost on the brink of his Golden Age, ran a course with a sinister but rather nebulous group, ‘The Brotherhood of Silence’ (a set of criminally-minded Trappists, perhaps?). Then there was Baron Robert de Beauremon and the Council of Eleven, (active just before and during the First World War but not at all afterwards, having been discarded from G H Teed’s repertory of villains), shortly followed by the Council of Nine who impinged a couple of times on the activities of George Marsden Plummer.

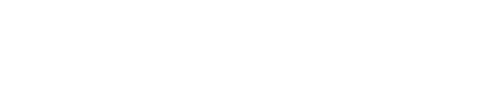

But the most dangerous gangs Blake encountered at the height of his popularity in the ‘twenties were the Double Four, led by the Ace (alias King Karl V of Serbovia who preferred master criminality to being Supreme Autocrat of his turbulent Balkan kingdom, which lay between Austria and Yugoslavia) and the Black Trinity. Blake encountered both these desperate bodies in The Union Jack in 1927 (The Double Four later reappeared in two volumes of The Boy’ Friend Library, but Blake and Tinker’s names were changed).

The King Crook was the brainchild of Gwyn Evans. After several encounters of mixed fortune with Blake, his hash was eventually settled by a revolution in Serbovia which deprived him of his immunity as a sovereign.

On formal — criminal — occasions, the King Crook wore a black domino mask with a sort of yashmak of Mechlin lace attached. The Black Trinity, however, favoured the more popular style of the Sinister Hooded Figure. Sinister Hooded Figures abounded amongst Sexton Blake’s adversaries as may be seen from many illustrations to the saga (they seem to have been even more prevalent in the pages of the Union Jack’s sister paper, The Thriller).

The Black Trinity was a creation of Anthony Skene and he told the story of Sexton Blake’s struggle with them in four consecutive issues of The Union Jack. In a preamble to the first episode, ‘The Coming of the Black Trinity’, we are told Blake’s campaign against them extended over about two years. All four episodes involve a good deal of violence and sudden death which is related in the cool and lucid Civil Service prose of Anthony Skene’s alter ego, Mr G N Phillips of HM Office of Works.

The Black Trinity lives by theft and murder. It rules its corner of the underworld by sheer terror. Failure or disobedience means death. Even mentioning the very existence of the Trinity is to incur death at their hands. Its methods are clumsy and brutal but effective. Blake became conscious of the Trinity as a new force in the underworld long before he heard a whisper of its name, though we never hear mention of any specific robberies it carried out. Its foot soldiers are apparently the remnants of the Sillox Gang, a bunch of racecourse toughs left leaderless after Sillox himself was “topped”. Blake eventually was told something — only the name of someone possibly involved with them — by a dying prisoner in Wormwood Scrubs. Blake had hardly returned to Baker Street, however, before he learned that the prison doctor and a “trusty”, who had both overheard the dying man’s words, had been murdered. Thereafter, Blake was involved in a headlong round of chases and attempts on his life until what was Round One of the battle ended with the death of one of the Trinity.

There is a pause, partly to enable the Trinity to regroup, partly — they hope — to lull Sexton Blake into a false sense of security. Then they make an attempt upon him as he leaves an East End police station. Their intelligence within the police — and, as we have seen, within the prison service — is evidently excellent. Blake captures the Trinity’s would-be assassin and forces the man to change clothes with him and then, while his prisoner is chloroformed, makes the man up as himself and himself as the thug. Blake now takes his captive to Smith’s, where the Black Trinity are meeting. There we meet our old friend Monsieur Zenith the Albino, in a cameo role, as a neutral observer of affairs at Smith’s, that surreal thieves’ kitchen which provides a luxurious subterranean rendezvous for the criminal classes with many secret entrances and exits beneath Essex Street in Islington (Building Smith’s must have been a considerable enterprise, since it must be greater than the Cabinet War Rooms and infinitely better appointed. I wonder if it’s still there, and in use? What a surprise it would be for the newer inhabitants of the district!).

There is a pause, partly to enable the Trinity to regroup, partly — they hope — to lull Sexton Blake into a false sense of security. Then they make an attempt upon him as he leaves an East End police station. Their intelligence within the police — and, as we have seen, within the prison service — is evidently excellent. Blake captures the Trinity’s would-be assassin and forces the man to change clothes with him and then, while his prisoner is chloroformed, makes the man up as himself and himself as the thug. Blake now takes his captive to Smith’s, where the Black Trinity are meeting. There we meet our old friend Monsieur Zenith the Albino, in a cameo role, as a neutral observer of affairs at Smith’s, that surreal thieves’ kitchen which provides a luxurious subterranean rendezvous for the criminal classes with many secret entrances and exits beneath Essex Street in Islington (Building Smith’s must have been a considerable enterprise, since it must be greater than the Cabinet War Rooms and infinitely better appointed. I wonder if it’s still there, and in use? What a surprise it would be for the newer inhabitants of the district!).

Blake had once before penetrated Smith’s in disguise in an earlier story by Skene. On that occasion when challenged, he had removed his disguise to reveal beneath it the features of Leon Kestrel, the Master Mummer. I mention this here to indicate Blake’s supreme mastery of disguise, so that his second exploit at Smith’s becomes credible. For a man who could adopt two disguises, one atop the other, and then remove one without disturbing that beneath it was surely a grand master of the art.

In the course of events, Inspector Coutts becomes at last convinced of the Black Trinity’s existence. This is a tale of rapid reversals of fortune and of Blake’s good fortune — Julia Fortune that is, a young lady, the daughter of a former ambassador to the Imperial Court at St Petersburg, and a leading light of our Secret Service (but whether MI5 or SIS is not made clear) who is a very useful deus ex machine for Blake in his last rounds with the Trinity. But why, in those interwar years, the secret service should interfere in domestic crime is unexplained

Blake has now learnt that the spokesman for the Trinity is not in fact its ringleader.

There is a hiatus between the second and third stories while the Trinity lick their wounds again and scheme to ruin Blake this time rather than kill him, first by attacking his investments which takes some time to organise, and then by fabricating evidence of a fur robbery against him with the aid of a corrupt official at the Yard. With the help of his loyal friend Inspector Coutts and of Julia Fortune who is, quite literally in at the death, they are again thwarted and at the end of this story the Black Trinity has become the Black Unity.

The final reckoning follows. Julia Fortune again plays a guardian angel role, saving Blake from death by chloroform.. She also finds that she knew the leader of the Black Trinity when they were girls in St Petersburg. For the elegant young man about town who proves to be the brains of the Black Trinity is a White Russian émigré transvestite, Lydia --- , we never learn the patronymic, and the body count at the end resembles a Jacobean tragedy, but our hero is triumphant.

I have not been too specific about the events of this series of eventful tales in case you should wish to read them for yourselves.

There is of course one problem that stories of vast criminal organisations led by unknowns always leave me with, and usually with no answer. If no one knows who the mastermind is, how does he get to start it and how does he maintain his anonymity, even if he/she is a White Russian transvestite?