THE ERIC PARKER STORY

by Derek Hinrich

For over twenty years, it was my good fortune and privilege to meet many Directors, Editors, sub-editors, authors, and artists, not only down Fleet Street, but in the offices of Fleetway House in Farringdon Street, the home of the mighty Amalgamated Press. I use the expression 'fortune' in the sense that, living in London, it was quite easy for me to make these short trips.

For over twenty years, it was my good fortune and privilege to meet many Directors, Editors, sub-editors, authors, and artists, not only down Fleet Street, but in the offices of Fleetway House in Farringdon Street, the home of the mighty Amalgamated Press. I use the expression 'fortune' in the sense that, living in London, it was quite easy for me to make these short trips.

Always firmly believing in sharing information with others not so fortunate, I used to write up many of these events in the various magazines circulating at the time. Nearly all personalities I'm glad to say, freely gave me information not only about themselves, but about the papers they were connected with in pre-war days. Papers that gave so much pleasure to us, as they do even today in some cases over a century later. Indeed, in time by so many meetings, many became good friends, and probably gave me real inside information, that they would not have revealed to the ordinary interviewer. The very sad fact today is that with all of them considerably older than myself — unfortunately the majority of them have passed on.

One man whom I shall always certainly remember with some affection was Eric Parker THE Sexton Blake artist. The word 'THE' is typed on my script in capital letters simply because it has often been said that at times the artist does as much as the writer to sell a paper. Nothing could he more truer in this case. Sexton Bake belonged to no single writer. Official records prove that about 200 odd writers have penned stories of the Baker Street detective since the first in the Halfpenny Marvel in 1893. It is true that quite a number of other artists portrayed the A.P. sleuth over the years including H.M. Lewis, Arthur Jones, J.H. Valda, Harry Lane, Val, E. Briscoe, C. H. Blake and W. Taylor, but none had a greater impact than Eric Parker when he came on the scene in 1922 in an Andrew Murray 'Union Jack' story entitled "Eyes in The Dark". For my own connection with this then new artist, one must start the events in sequence ...

I first met Eric Parker on one of the upper floors in Fleetway House in the late fifties. I was waiting for the lift to take me from the sixth to the ground floor. Almost everyone has experienced the same frustration that the lift is usually everywhere else except the place where you are standing. A well-dressed middle-aged man was waiting with me, who also tutted with annoyance at the delay. I agreed with him and recognising him as Eric Parker by photographs I had seen of him said modestly "that I believed he was Eric Parker, the Sexton Blake artist". A sort of twinkle came into his eyes as he replied "I guess you are Bill Lofts, whom Bill Baker was telling me about - who knows all the answers about Sexton Blake". Eric went on "By the way who is that new big office boy he has got, who asks me questions about the old Union Jack". I replied that it was "Mike Moorcock, one time member of the London Old Boys' Book Club, and an enthusiast especially of Edwy Searles Brooks". (Mike today is world famous for his science fiction and fantasy stories, at least one of his books being filmed.) Eric then invited me to have a quick drink with him at the 'Swan', before he had to dash off home for some appointment. Meeting him unexpected I was not primed to ask him much at this short meeting, but we had promised to meet again in the future when he had more time.

We met many times after this, mostly with Howard Baker, or with a group of other old A. P. editors, artists, and authors. Once I remember with Dan O'Herlihy the film actor who has now almost a complete set of Magnets and Gems — and was a great admirer of his work. We also met in the Directors' room at Fleetway House to celebrate the return of Sexton Blake in a picture strip in the new boys picture paper 'Valiant' as well as the coming T.V. series. Gerald Verner, the Blake writer, was present along with other personalities including Brian Doyle. Another sad party that one must call it, was the closing down of the Sexton Blake Library in 1964. Another very unique event was when I walked the whole length of Baker Street with him to catch a bus at the Regents Park end for his home at Mill Hill. Eric was most keen to know exactly where Sexton Blake was supposed to have lived, but I must confess that, while the home of his great rival Sherlock Holmes could be pinpointed, no number was ever given to my knowledge of the house kept by Mrs. Bardell, though my own theory is that it was probably near Marylebone Circus, not far from Baker Street Station.

In appearance Eric Parker was stockily built on the lines of E. S. Brooks with a pleasant type of face, looking much younger than his actual years. Always neatly dressed either in a grey tweed suit or sports jacket with tie, he had neat grey hair with a small moustache. Another characteristic I noted was that he favoured blue shirts, whilst on special events a flower in his button-hole. I can well remember him wearing a white carnation at the Sexton Blake farewell party. Basically I had the impression that he was by nature a shy man, rather guarded in answering questions with a far-away look in his eyes until he got to know you. All in all I would describe him as a genial type of person, a good companion, and with a good sense of humour.

Eric Robert Parker to give him his full name was born at Stoke Newington, North London, on the 7th September, 1898. According to his own recollections, there was no other artist in the family. His father was a clock-maker, as was his father before him. As a boy he attended an L. C. C. school, when at the age of fifteen, he had the great honour of being the very first London County Council schoolboy to be awarded an Art Scholarship with a maintenance grant, then attending the Central School of Art. Indeed, in The Boys' Own Paper cir. 1913 there was a small photograph of him, giving praise for his rare achievement. I can well remember loaning Leonard Matthews the Director of Juvenile Publications at Fleetway House this volume — he proudly showed it to editors who were using his work. His first published work was believed to be a set of pictures for postcards in 1915, then the First World War called him, and he served in The Bucks Hussars.

Eric Robert Parker to give him his full name was born at Stoke Newington, North London, on the 7th September, 1898. According to his own recollections, there was no other artist in the family. His father was a clock-maker, as was his father before him. As a boy he attended an L. C. C. school, when at the age of fifteen, he had the great honour of being the very first London County Council schoolboy to be awarded an Art Scholarship with a maintenance grant, then attending the Central School of Art. Indeed, in The Boys' Own Paper cir. 1913 there was a small photograph of him, giving praise for his rare achievement. I can well remember loaning Leonard Matthews the Director of Juvenile Publications at Fleetway House this volume — he proudly showed it to editors who were using his work. His first published work was believed to be a set of pictures for postcards in 1915, then the First World War called him, and he served in The Bucks Hussars.

After the war, he contributed to The Strand Magazine, and similar type of publications, but nothing was really permanent, until one day in 1921 he submitted samples of his work to the Amalgamated Press Ltd., when here was to begin an association that was to last for over fifty years, and right up to his death. Harold William Twyman had just taken over the editorship of The Union Jack from Walter Shute — better known as "Walter Edwards" the well-known boys' writer. They say that 'a new broom sweeps clean', when up to that date quite a number of artists had been used to portray Sexton Blake — H. M. Lewis, Arthur Jones, J. H. Valda, Harry Lane, Val, E. Briscoe, C. H. Blake, and W. Taylor — 'Twy', as he was called, wanted someone more regular — someone whose drawings readers could easily identify as the Baker Street sleuth. He recognised at once that he had a real find in Eric Parker, so persevering with him, in time he was drawing the characters almost every week, other artists just appearing from time to time. Eric told me that he had actually based his Sexton Blake on a commercial traveller he once knew at a club. He used to sit alone, a tall distinguished figure, making a big impression on his mind. He was also lean, smoked a pipe, and had slightly receding hair.

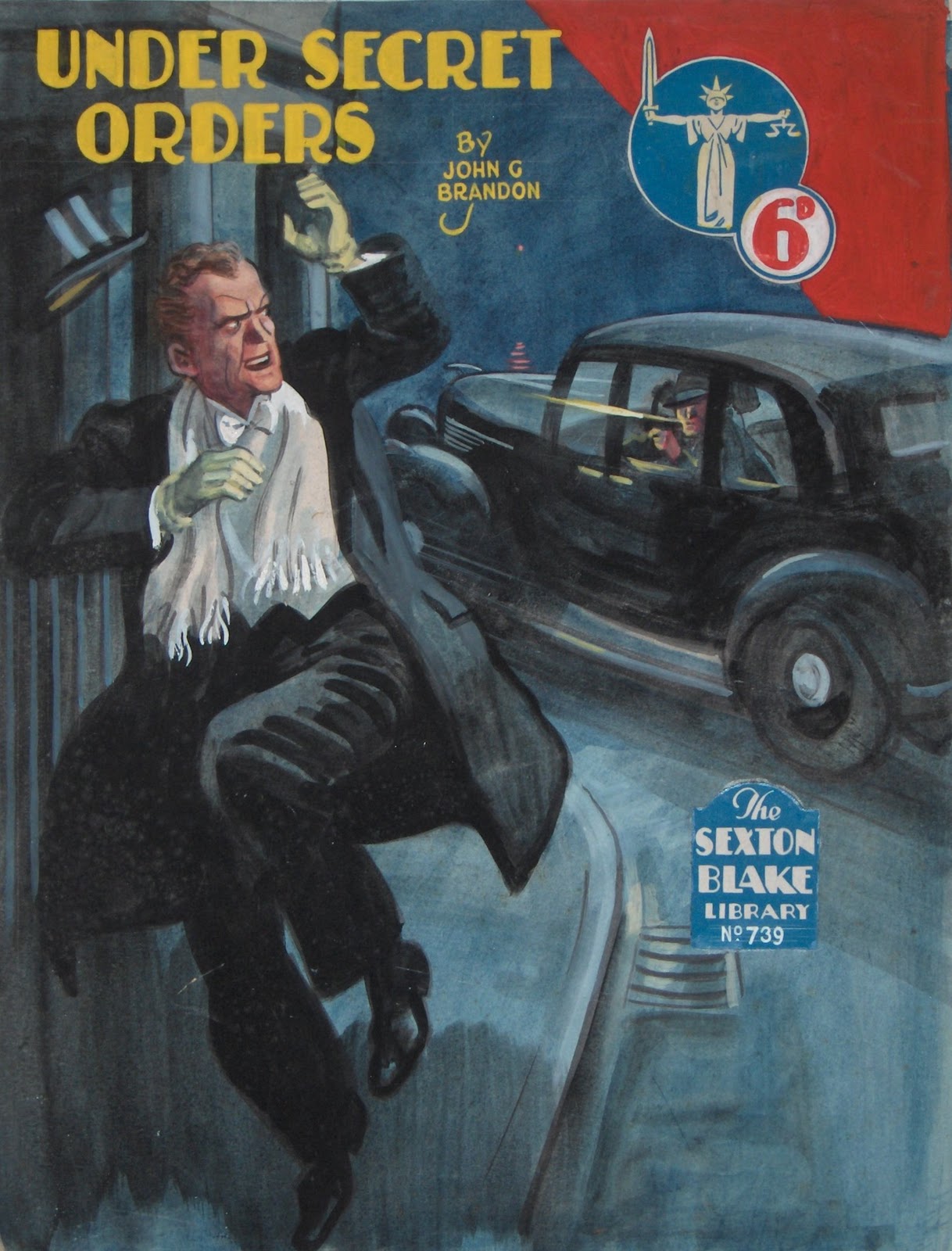

Parker's work became so popular with readers, that in 1930, Len Pratt who was editing The Sexton Blake Library, also made use of his services when he drew four covers each month right up to 1940, when the paper shortages cut this quota down to two. Even when the old Union Jack ceased in 1933 being renamed Detective Weekly he continued drawing the covers, as well as the inside illustrations.

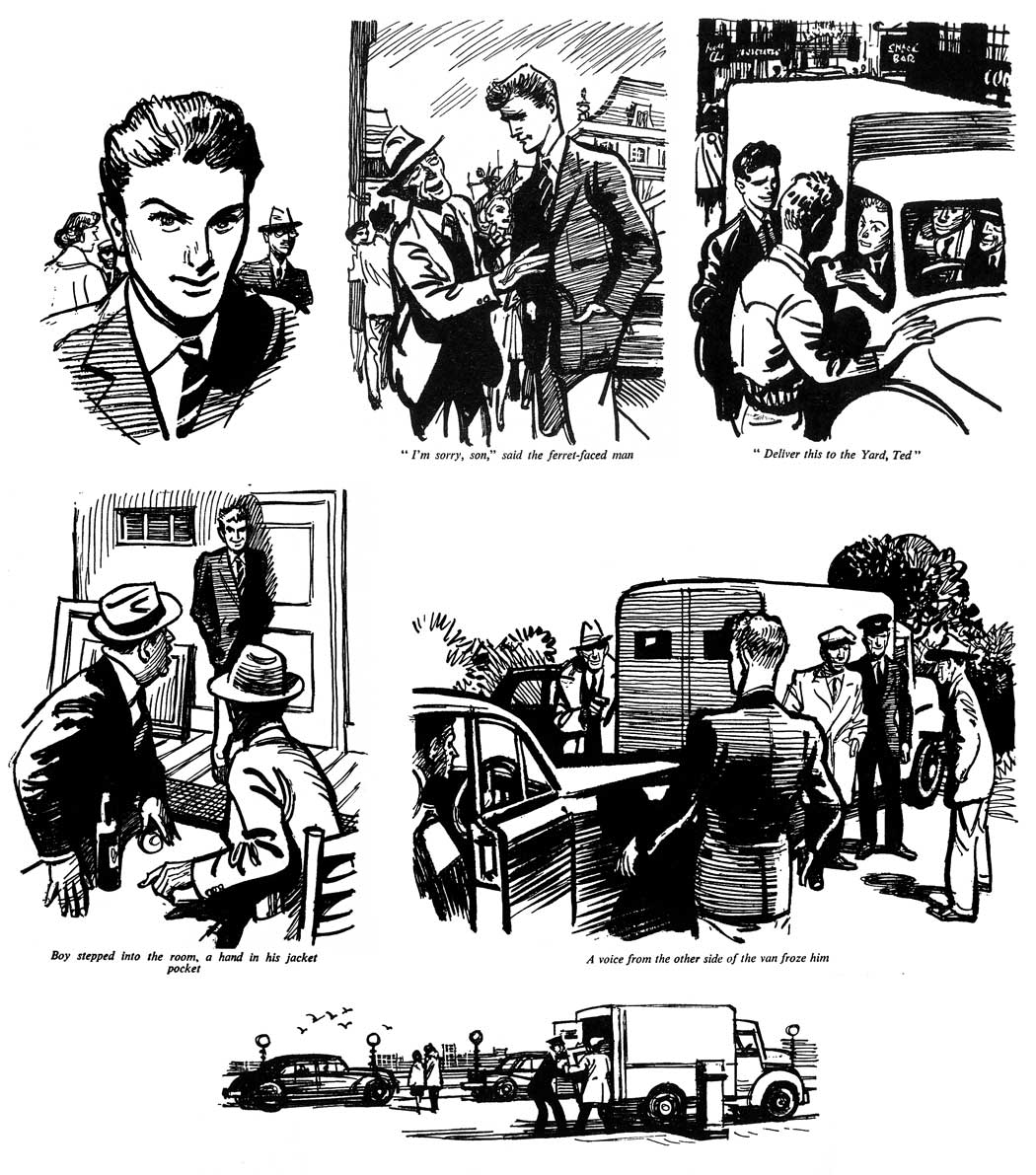

Eric Parker's work to the professional fellow artist was always considered brilliant. It had the impact similar to watching a film, his fine draughtsmanship being matched by very clever characterisation.

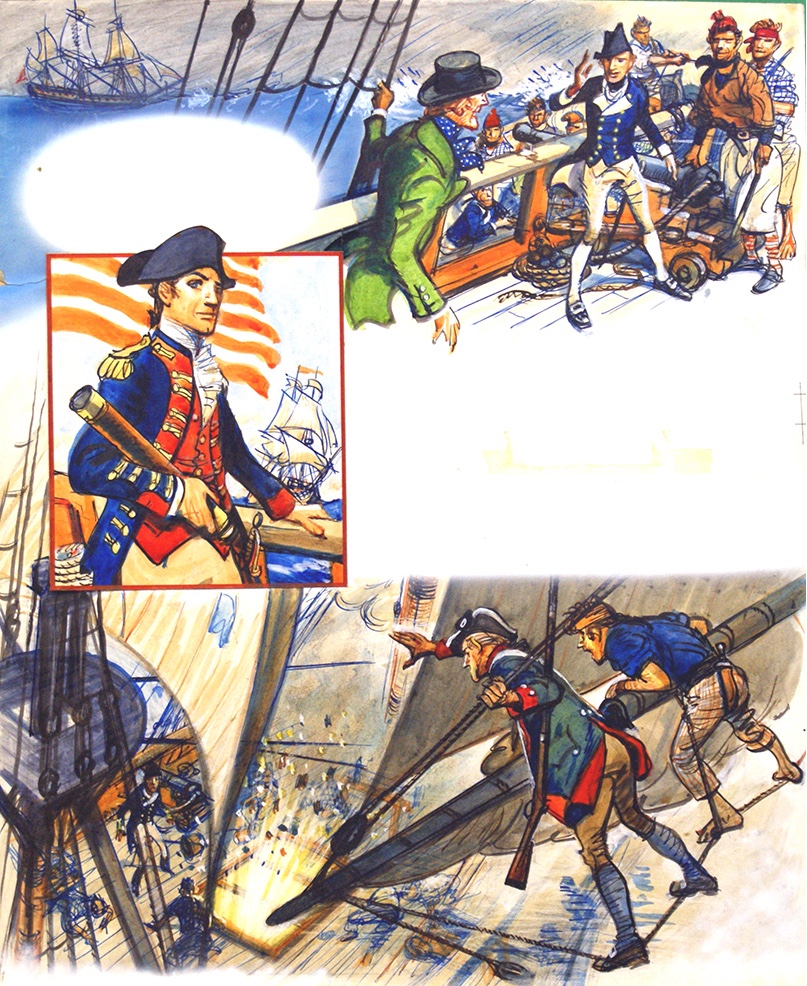

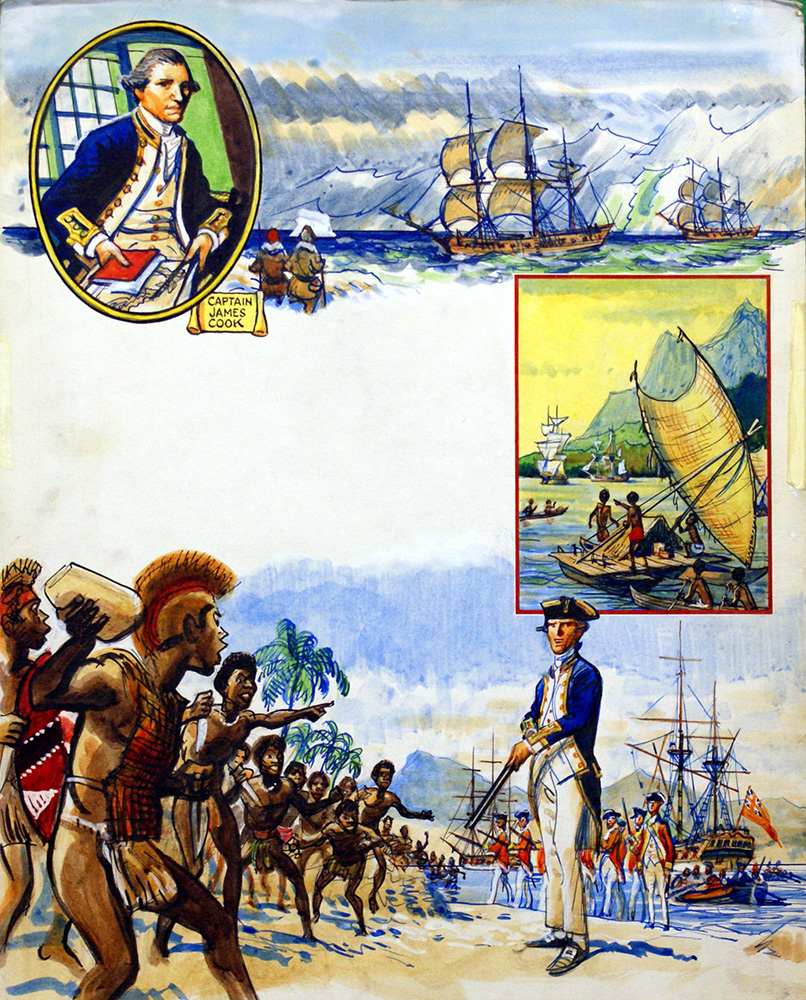

He had the gift of drawing the layout exactly right, perfect in background detail without cluttering it up with unnecessary objects. One could conjure up in the mind what type of house it was by just looking at the door, or by say a dingy looking street, the whole area where the action was taking place. Atmosphere could also be said to be the secret of his power, as well as the clothing of his characters being exactly right, right for the character, circumstances, season and period. If there was a car in the sketch, you can bet it was the latest model if the scene was of current times — he was actually a keen motorist with a taste for racy models. Was there a girl in the sketch? Well if she was young looking — and Eric could draw very shapely young girls — you can bet she had on the latest dress of fashion. Once he had to draw a Chinese villain, when any other artist would have probably drawn him (especially in the twenties) in Mandarin dress — somehow like Wun Lung in the early days at Greyfriars. Eric, bang up-to-date, had his Chinese in evening dress that would have graced the Ritz Hotel, which as it happened tallied with the description in the story. Another classic example of his skill, could be taken not by Sexton Blake, but by his portrayal of Detective Inspector Coutts who appeared in so many of the stories. Coutts looked aggressive, cocksure, burly and exactly as the writers had described him. In other fields of drawing, his historical scenes were authentic, even down to the design on the tunic buttons on his Napoleonic uniforms. To sum up his work in general, he made brilliant use of shadows to give a dramatic and mysterious effect, plus the right colour sense. His style could be said to be unique, and I could never remember him telling me that he based his work on another, nor been influenced by someone in the past. Nor could any other artist be found whose work resembled anything like his own.

He had the gift of drawing the layout exactly right, perfect in background detail without cluttering it up with unnecessary objects. One could conjure up in the mind what type of house it was by just looking at the door, or by say a dingy looking street, the whole area where the action was taking place. Atmosphere could also be said to be the secret of his power, as well as the clothing of his characters being exactly right, right for the character, circumstances, season and period. If there was a car in the sketch, you can bet it was the latest model if the scene was of current times — he was actually a keen motorist with a taste for racy models. Was there a girl in the sketch? Well if she was young looking — and Eric could draw very shapely young girls — you can bet she had on the latest dress of fashion. Once he had to draw a Chinese villain, when any other artist would have probably drawn him (especially in the twenties) in Mandarin dress — somehow like Wun Lung in the early days at Greyfriars. Eric, bang up-to-date, had his Chinese in evening dress that would have graced the Ritz Hotel, which as it happened tallied with the description in the story. Another classic example of his skill, could be taken not by Sexton Blake, but by his portrayal of Detective Inspector Coutts who appeared in so many of the stories. Coutts looked aggressive, cocksure, burly and exactly as the writers had described him. In other fields of drawing, his historical scenes were authentic, even down to the design on the tunic buttons on his Napoleonic uniforms. To sum up his work in general, he made brilliant use of shadows to give a dramatic and mysterious effect, plus the right colour sense. His style could be said to be unique, and I could never remember him telling me that he based his work on another, nor been influenced by someone in the past. Nor could any other artist be found whose work resembled anything like his own.

Another unique skill of Eric Parker, was the Sexton Blake bust that in 1926 was given away free to readers in a token scheme in The Union Jack. This was the first attempt by Eric of sculpturing, and what a good job he made of it. When the original clay model had been completed and was waiting in the Editorial office to go to the pottery it was still soft and inclined to sag, so a pencil had to be stuck up the back of the head to keep the nose part from slipping! About 850 busts were made originally by Regali & Son of Clerkenwell — a place I visited some years ago to have one old bust repaired. After the token scheme had finished, about 100 busts were still remaining in the office — so they were laid out like a wall. They gradually disappeared, mostly with the departure of hard-up authors who had visited the office — and were tempted perhaps of getting a free drink in exchange for them in the taverns of Fleet Street! Unfortunately, these busts were made of very cheap plaster, so that they were easily broken, and only about a round dozen are known to exist today. Amusingly in the fifties, some important Roman and Greek remains were found in the City of London — belonging to the Temple of Mithas. Not long afterwards there was a battered old broken Sexton Blake bust exhibited in a back street antiques shop window as coming from the newly dug up remains!

Once I asked Eric, "who was the best artist that the old Amalgamated Press ever had?" and he replied with his great sense of humour "Why Eric Parker of course!" — but seriously he was always greatly interested in Warwick Reynolds the First World War artist; he also seemed to favour St. Jim's as he also liked the main Gem artist R. J. MacDonald with his boys with large French bows as he called them. He seemed to have no time for, or ever wanted to discuss comic artists or the work of C. H. Chapman — he called him 'The Billy Bunter Man' — a name that the Greyfriars illustrator was known as at Fleetway House. Eric did read some of the Sexton Blake tales he illustrated, his favourites being G. H. Teed and Rex Hardinge though I never got round to asking him what he had read himself when a boy.

In the thirties, he extended his work even further, when he illustrated for Cassells' "Chums" and Pearson's "Scout", being also in the very fortunate position to turn work down — such was his busy schedule. The coming of the Second World War meant the closing of many of the Amalgamated Press papers, but such was the high esteem of his work, that when the 'Detective Weekly' went, he was able to contribute to 'Knockout Comic', including later on in 1949 the Sexton Blake picture strip. Maybe he was also fortunate in the fact that the then editor of 'Knockout' was Leonard Matthews, who not only greatly admired his work, but both shared the same great interest in the Napoleon period of history. He certainly made great use of his authentic and expert knowledge in later publications such as 'Look and Learn', 'Thriller Comics', and the comic 'Comet'.

Around this period he also worked for the Ministry of Information like so many other artists who wanted to do their share of war work.

Around 1955 came another type of bombshell, when Len Pratt the editor of The Sexton Blake Library, retired after forty years service. Again, as in 1921, a new broom swept clean, but this time to Eric Parker's disadvantage, when the new temporary editor, David Roberts, employed new artists. Maybe to be fair, he was only acting on orders from a higher authority, as it was widely known that the image of Sexton Blake was to be altered to bring him up-to-date for the modern generation Consequently, when eventually W. Howard Baker was appointed the new editor a year later, Parker had long left the Library, and was working in other departments at Fleetway House. One, in a way, must be fair to Howard Baker, for although he had strict instructions to modernise Blake, such was the demand by old readers for E.R.P's return that he did use him as much as possible on very special occasions. Certainly the most original drawing that Eric ever produced was a picture showing all the contributors at a party to celebrate the third anniversary of the New Look Sexton Blake. As I knew personally the majority of people in this illustration, I can vouch for the amazing likeness of all those present. It has often been said that our artist could not draw faces, with especially all his male characters having hatchet type of features, and this certainly proved them wrong. Howard Baker for instance was at least four inches taller than Eric Parker, and to see them in this illustration standing side by side, was exactly as I remembered them, and like looking at a photograph.

Around 1955 came another type of bombshell, when Len Pratt the editor of The Sexton Blake Library, retired after forty years service. Again, as in 1921, a new broom swept clean, but this time to Eric Parker's disadvantage, when the new temporary editor, David Roberts, employed new artists. Maybe to be fair, he was only acting on orders from a higher authority, as it was widely known that the image of Sexton Blake was to be altered to bring him up-to-date for the modern generation Consequently, when eventually W. Howard Baker was appointed the new editor a year later, Parker had long left the Library, and was working in other departments at Fleetway House. One, in a way, must be fair to Howard Baker, for although he had strict instructions to modernise Blake, such was the demand by old readers for E.R.P's return that he did use him as much as possible on very special occasions. Certainly the most original drawing that Eric ever produced was a picture showing all the contributors at a party to celebrate the third anniversary of the New Look Sexton Blake. As I knew personally the majority of people in this illustration, I can vouch for the amazing likeness of all those present. It has often been said that our artist could not draw faces, with especially all his male characters having hatchet type of features, and this certainly proved them wrong. Howard Baker for instance was at least four inches taller than Eric Parker, and to see them in this illustration standing side by side, was exactly as I remembered them, and like looking at a photograph.

Whilst on the subject of drawing the likeness of faces, it is worth mentioning that Eric usually carried a stub of pencil in his pocket to illustrate any point he was making. I can well remember telling him how I thought that H. W. Twyman the 'Union Jack' editor, reminded me in some ways of Sexton Blake. My assumption being based simply on the fact that he was rather tall, had a lean figure, and similar hair style that was receding at the temples - though 'Twy' did wear glasses that spoilt the image to some extent. Eric thought differently mainly on the facial structure, and drew me a small pencil sketch of how he remembered 'Twy'. As he had not seen him for over twenty years, and I had met him only a few weeks previous, the likeness was uncanny. This drawing was later reproduced on the cover of an issue of the Australian 'Golden Hours' magazine. Twyman's reaction in seeing the sketch was also most interesting ...

"When I first saw it. I wondered who it was supposed to represent, but few people know what they look like in profile, and are mildly shocked when they go to the tailors and see themselves in that tricky arrangement of mirrors, I am one of them, but from various indications in the sketch itself I soon tumbled.

He made it something between a portrait and a caricature, and the whole thing is very clever. It's interesting, and a bit flattering, that he should be able to carry in his mind's eye all this time the little characteristics that would build up what is, I feel, an essential likeness. No other artist of my acquaintance had such wonderful observation and dexterity — and I knew others besides A. P. men, who were, by far and large, just tradesmen. It happened I was the first to recognise Eric Parker's quality, and the first editor to buy his work, but I think his skill was wasted in the cheap market (though it was certainly developed there) and that he should have had a more distinguished career.

With his thoughts no doubt rekindled with memories of Eric Parker, on a later visit to Mr. Twyman, I was most interested to learn that he had remembered something that might be of great interest not only to myself but to other collectors of Sexton Blake material. During his period of office as Union Jack Editor, it was his practice to take home with him art-work of Eric Parker that had been returned from the printers. He used to store this in his loft at his home at Benfleet in Essex. On leaving the Amalgamated Press towards the late thirties, and having to sell his house in a great hurry, as well as losing his interest in Sexton Blake, he left this Parker material behind. If the owner had not discovered this and the house had survived the heavy bombing by the German Air-Force there was a faint chance that the paintings could still be there. Drawing a map of where the house stood plus giving me the owner's name, on a visit a few days later I found the house still standing with the owner still in residence after 25 years. He at first was very suspicious of me as there had been a lot of burglaries recently. After convincing him that my call was genuine he told me that unfortunately during the last war the whole roof had been set on fire by a fire bomb and had been completely destroyed. As it happened they had not used the loft and no-one knew the paintings were there. I left Benfleet and journeyed back to Fenchurch Street a very sad man, realising that some unique original illustrations had now been lost for all time.

With his thoughts no doubt rekindled with memories of Eric Parker, on a later visit to Mr. Twyman, I was most interested to learn that he had remembered something that might be of great interest not only to myself but to other collectors of Sexton Blake material. During his period of office as Union Jack Editor, it was his practice to take home with him art-work of Eric Parker that had been returned from the printers. He used to store this in his loft at his home at Benfleet in Essex. On leaving the Amalgamated Press towards the late thirties, and having to sell his house in a great hurry, as well as losing his interest in Sexton Blake, he left this Parker material behind. If the owner had not discovered this and the house had survived the heavy bombing by the German Air-Force there was a faint chance that the paintings could still be there. Drawing a map of where the house stood plus giving me the owner's name, on a visit a few days later I found the house still standing with the owner still in residence after 25 years. He at first was very suspicious of me as there had been a lot of burglaries recently. After convincing him that my call was genuine he told me that unfortunately during the last war the whole roof had been set on fire by a fire bomb and had been completely destroyed. As it happened they had not used the loft and no-one knew the paintings were there. I left Benfleet and journeyed back to Fenchurch Street a very sad man, realising that some unique original illustrations had now been lost for all time.

It wad during the fifties that Eric Parker first contributed to newspaper strips such as 'Pepy's Diary' in the now defunct London Evening News. 'Making a Film', and 'Paula' in the Daily Express — as well as 'An Age of Greatness' in the Daily Graphic. He also contributed to The Daily Mail Annuals. For some reason, about 1960, he always seemed to be worrying about the standard of his work, and whether he was slipping a bit. Whether he had for the very first time had something rejected I do not know, but he also seemed concerned that he was not on the Amalgamated Press staff, and therefore would not qualify for a pension when he decided to call it a day. I assured him that I would put in a good word for him to the powers that be — should the need arise, emphasising the fact that he had given over 40 years faithful service to the same firm. Next, to my surprise, and I will never know if my 'hints' had done the trick in the right places, but I heard he had been appointed an Art Director at the now Fleetway Publications, where his brilliant ideas and layout were used to just sketch roughly for other lesser artists to polish and colour. Actually he had been given a similar position to that of Bert Brown the famous comic strip artist (of Charlie Chaplin, Pa Perkins, Dad Walker, and Homeless Hector fame) who was a genius at amusing ideas and comic situations.

Personally I thought that this would be the ideal job for Eric in the twilight of his career, as like all human beings his work was bound to lose its edge in the passing of the years. But to be truthful, he really hated being cooped up in an office with its dull routine. After forty years as a free-lance, it was like a wild bird being trapped in a cage. In fact he used to get out of Fleetway House as often as he could to get some fresh air.

Some years ago, an enthusiast estimated that Eric Parker had produced a run of no less than 900 covers in the Sexton Blake Library alone. Adding to this his work on the Union Jack, Detective Weekly, and Sexton Blake Annuals, plus the many thousands of inside illustrations, chapter headings, and tail pieces — his output was really astonishing. A quick and deeply conscientious worker, he usually delivered four Sexton Blake Libraries at a time, and was always on schedule. Indeed, he thought so much of always being on deadline that often he would delay his holidays because of pressing work — much to the despair of his wife Beatrice and daughter. Married in 1929, it should be recorded that his wife helped him a great deal in not only keeping the books, but delivering art-work on his behalf when he was too busy to go in to town himself.

Some years ago, an enthusiast estimated that Eric Parker had produced a run of no less than 900 covers in the Sexton Blake Library alone. Adding to this his work on the Union Jack, Detective Weekly, and Sexton Blake Annuals, plus the many thousands of inside illustrations, chapter headings, and tail pieces — his output was really astonishing. A quick and deeply conscientious worker, he usually delivered four Sexton Blake Libraries at a time, and was always on schedule. Indeed, he thought so much of always being on deadline that often he would delay his holidays because of pressing work — much to the despair of his wife Beatrice and daughter. Married in 1929, it should be recorded that his wife helped him a great deal in not only keeping the books, but delivering art-work on his behalf when he was too busy to go in to town himself.

The very last time I saw Eric, was when he was taking some of his 'fresh air' and walking along the Embankment. His blue-grey eyes lit up when he saw me. "Got time for a drink, Bill?" was his first remark, but unfortunately I had to decline, as I was late for an appointment at The Daily Mail. Eric hid his disappointment, and said as genial as ever "Next time, then Bill!" Unfortunately there was never a next time, as I learned later that he had died at Edgware General Hospital of double pneumonia on the 21st March, 1974, when he was 76 years old.

I suppose I walk through Fleet Street and by the old Amalgamated Press building site almost daily. I often think of the many friends I used to meet in the various taverns, and especially up in Fleetway House. Sometimes I forget that the years have gone so quickly and the familiar figure of Eric Parker — as well-groomed as ever — will come round the corner. He'll give me a friendly smile, and then we will have an enjoyable evening talking about the good old days.

It was not only my pleasure to know Eric as a friend, but also as one of the best boys' paper illustrators in the history of detective and thriller publications. May he never be forgotten.

© W. O. G. Lofts